This article is from the Occupied News Wire. It originally appeared in the Occupied Oakland Tribune.

By Scott Johnson – @OakScott

For nearly 150 years, May 1st has been an international day to celebrate and defend the rights of the working class. While the immigrant rights movement and the Occupy movement have helped bring it back to the United States in recent years, May Day originated in the American labor movement in the 19th century.

The first mass labor protest on May Day was held in 1867 to celebrate an Illinois law mandating an eight-hour workday. When employers refused to abide by the law, the celebration turned into a rebellion. Chicago police, “long used as if [they] were a private force in the service of the employers,” as one author would later declare, were called on to break the strike wave. The movement was crushed and the law went unenforced.

After nearly two decades, May Day was resurrected when the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the United States and Canada (later the AFL) proposed that “eight hours shall constitute a legal day’s work from and after May 1, 1886.”

Even more significant than the Federation was the Knights of Labor, whose motto was “An injury to one is the concern of all.” The Knights opposed wage labor and believed in solidarity for all workers, regardless of race, gender or skill-level. However, the Knights were held back by the conservative leadership of Terence Powderly, who opposed going on strike for the eight-hour day and instead called on workers to write letters on the subject to be printed in newspapers on George Washington’s birthday.

Regardless, hundreds of thousands of workers joined the Knights expecting militant action on May Day. Their membership grew from 28,000 in 1880 to 700,000 in 1886. Powderly even put a moratorium on new chapters and suspended organizers to halt this growth in numbers and expectations. “The majority of the newcomers were not of the quality the Order had sought for in the past,” Powderly complained of these militant new recruits, but the Knights grew in spite of his efforts.

Nonetheless, anarchists and socialists continued to organize for a strike – and not a letter writing campaign – on May Day. Among the best known radicals was Albert Parsons, a Confederate soldier at 14 who later published a pro-Reconstruction newspaper in Texas that defended the rights of newly freed slaves. Moving to Chicago, the center of workers’ struggle, he participated in the national railroad strike of 1877, leading to him being blacklisted and his life threatened for being the “leader of the American Commune.”

By April of 1886, the hunger for an eight-hour day grew with 62,000 workers in Chicago pledging to strike, 25,000 demanding an eight-hour day without committing to a walk out and 20,000 already winning a reduction in their hours. Workers wore “eight-hour shoes” and smoked “eight-hour tobacco” in solidarity with workers who already won their demands. As the strike approached, the demand grew from a reduction in hours from eight to ten, to “eight hours of work for ten hours pay.”

On May 1, 340,000 workers across the country marched with 190,000 of those going on strike. New York saw a rally of 20,000 workers in Union Square – the recent home away from Zuccotti Park for Occupy Wall Street – and there were 10,000 each in Baltimore and Chicago.

The rebellion continued through May 3 when a confrontation with strikebreakers in Chicago resulted in police shooting and killing 4 workers and injuring many others.

On May 4, 1,200 workers gathered at Haymarket Square in Chicago to hold a meeting about the police killings. The number in attendance declined to 300 due to rain and Parsons left with his wife and children. The mayor of Chicago, also in attendance, even told the police – who were prepared to break up the event at any time – that it was a peaceful meeting and there was no need to attack it.

Suddenly, nearly 200 police officers stormed the meeting with no provocation or warning. Just as suddenly, dynamite was flung toward the police and exploded, killing one instantly and wounding 70, seven of them fatally.

In the following days, a full scale war was declared on the labor movement – meetings were broken up, radicals arrested and the strike wave was crushed as the jails were filled with the radical leaders of the workers’ movement.

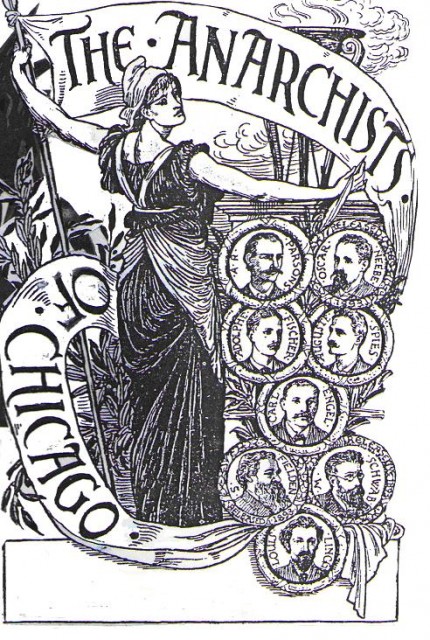

Eventually, seven people were singled out and tried for killing the police officers, even though there was no evidence that they had any role in the bombing, which may have been carried out by a provocateur. Some of the accused were not even in attendance at the time of the explosion but that hardly mattered, as the Chicago establishment openly stated.

“Law is on trial. Anarchy is on trial,” declared Julius Grinnell, the prosecutor in the case against the Haymarket martyrs. “These men have been selected, picked out by the grand jury, and indicted because they are the leaders. They are no more guilty than the thousands who follow them. Convict these men, make examples of them, hang them, and you save our institutions, our society.”

Ultimately, seven men were sentenced to death and another to 15 years in prison. But rather than hide from the accusations of radicalism, they defended their views at trial. “I am an Anarchist,” announced Oscar Neebe. “What is Socialism or Anarchism? Briefly stated it is the right of the toiler to have the free and equal use of tools of production and the right of the producers to their product. That is Socialism.”

Another defendant, August Spies, told the judge upon being sentenced, “If you think by hanging us you can stamp out the labor movement…the movement from which the down-trodden millions, the millions who toil in want and misery, expect salvation – if this is your opinion, then hang us! Here you will tread upon a spark, but there and there, behind you and in front of you, and everywhere, flames blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out…”

An international campaign was launched to defend the Haymarket martyrs, led by Parsons’s wife Lucy, a former slave and a revolutionary herself, but to no avail. On November 11, 1887, Parsons, Spies, George Engel and Adolph Fischer were executed. “Hurrah for anarchy!” shouted Engel from the gallows.

A fifth died in prison, committing suicide by exploding a stick of dynamite in his mouth, and two others had their sentences commuted to life in prison.

But the “subterranean fire” could not be put out. The struggle against capitalism continued, ultimately winning a shorter working day as mass strikes were organized by workers throughout the 19th and 20th centures, inspired by the martyrs who led one of the greatest rebellions of American workers.

1 comment for “A Brief History of May Day”