Story and photo by Pete Shaw

History, it is said, is written by the victors. Their perspective and their stories are presented as unimpeachable. From this favored perch, the present is interpreted and the path to the future is mapped.

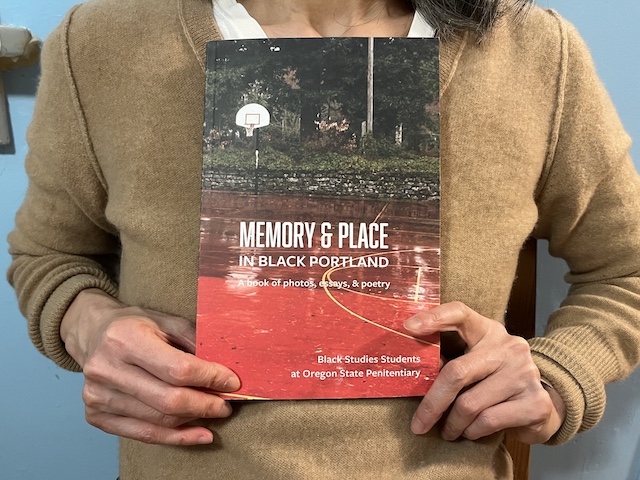

A new book, Memory & Place in Black Portland, adds its voice to the long and rich legacy of those challenging this privileged narrative. The history described in it is that of the Black community and culture that once thrived in North and Northeast Portland, particularly in Albina where the majority of Black people settled following World War II and the Vanport Flood of 1948.

The book–a moving collection of photos, essays, and poems brought together by Portland State University (PSU) Black Studies students who are incarcerated at Oregon State Penitentiary–offers cherished narratives from traditionally underprivileged voices, touching on place as palpable presence. Parks, restaurants, basketball courts, grocery stores, the back halls of Lloyd Mall–these and more play starring roles alongside the feelings and memories they conjure. These students breathe life and lives into them, illuminating the photographs taken by students in PSU’s Project Rebound, which supports formerly imprisoned students as they transition from prison to college.

“Whatever forces of gentrification and so much more attempt to change or eradicate the physical landscape,” said Walidah Imarisha at the photo exhibit and book release celebration on January 26, “these students have saved and preserved these parts of Portland for all of us and for future generations to come.”

Imarisha and Dr. Lisa Bates, both instructors in the Black Studies Department at PSU, and Nahlee Suvanvej, the director of PSU’s Higher Education in Prison program, worked with these students in prison to produce the book.

Bates said that one of the impulses for the project was 2020’s reigniting of the fight to abolish police, prisons, and “punitive and carceral measures as a really false way to try to get to community safety.” PSU’s Black Studies and Urban Studies programs concluded the best people to ask about these issues were “the people who have individually been directly affected by, impacted by, the criminal legal system.” An advisory group was convened to come up with a project to ask people who have been imprisoned what community safety means to them and what is needed “to move forward in our collective endeavor toward a different way of being.”

Bates noted that Babatunde “Zubbi” Azubuike, Executive Director of the Black & Beyond the Binary Collective, described that different way of being, “In a truly safe, community centered future, there would be no place that love cannot find you. That’s when we would really be safe.”

“It’s a metaphorical place,” said Bates, “but it’s also real geographical places. It’s real neighborhoods and communities. We worked with our advisory group recognizing the power of Black neighborhoods and Black places as centers of love, of nurturing, of nourishing people. Outside of systems of police that weren’t keeping people safe. But within systems of family, neighbors, kinship, in very special, actual geographic places here in Portland.”

That sense of a desire, sometimes leaning toward a desperate yearning, to belong to something that loves and can be loved permeates this collection. Elijah Craig finds it in the mall in “Lloyd Center.” As a kid, he trails his grandma to the Newberry’s Thrift Store behind the mall. Later, he navigates crowds smelling of “overly priced colognes” and takes advantage of free food samples that “poverty always pulled me toward.” He is not like many of the shoppers, whether there to purchase the latest Air Jordans, or “in a hurry to buy nothing.” Rather, his purpose there is to find

My mother fresh out of prison

Only job available was mall janitor

Somehow those food court visas

Was better than Columbia River Visitation

In his essay following the poem, “MLK & Killingsworth,” appearing below a Lisa Gursich photo of the intersection, Craig meditates on “the backbone of the Portland Black Community.” Yet most of it, the houses and the businesses, were not Black owned. Landlords and businesses catered to Black people and their community, but the wealth Black people and the Black community created went elsewhere. While the photo reminds Craig of fun times spent with family and making “things/places and sounds nobody wanted” at the time, he pines for a world where the society that “already copies and follows” what Black people and Black communities create, treats them equally instead of voicing support while passing “the same laws that keep us at the bottom and stuck in intersections of MLK & Killingsworth, poverty.At other times, family and community, or at least the values which undergird the best of those concepts, are temporary, but their meaning can never be understated. In “U-Haul,” Jeffrey Sanders describes the daily grind of heading to work each day. The work itself is left unmentioned. The poem provides a sense of place familiar to any Portlander: the rain and the smell of pines. These remind him of his grandfather who taught him to work hard. He has passed, but he remains inside Sanders, a guiding light.

Arriving to work on time–before time–and doing a job as best one can is not an end to itself. It includes helping raise his own family. In Sanders’s essay “The Service of People,” it also means doing good unto others because you should. Perhaps it is what you must do. It has been passed down through the generations. The essay is perfect in every way, while set in a place that firmly is not.

The call of home, wherever and whatever that may be, rings loudly, often desperately, in this collection–whether from a literal jail cell, or in the day to day violence of white supremacy, such as noted in Craig’s work, and more pointedly in Dwayne McClinton’s poem and narrative, both titled “Gentrification.”

McClinton grew up in a house on NE 16th and Prescott, a stone’s throw from Alberta Street, a place that has frequently been tagged as the poster-child for Portland gentrification. In his poem, McClinton’s house–his home–is “full of good and bad memories/But they are all cherished.” In its 32 pulsating lines McClinton names names and calls out the crimes of erasure.

Then I instantly thought about

gentrification

The process to push the Blacks out of our

neighborhood

Their urban renewal plan

White racists pressing

The Portland Development Commission

Now Prosper Portland, destroying Black

communities

Stealing homes, businesses, land, history

and wealth

Any conversation of community and culture, whether through enthusiasm or appetite, inevitably turns to food. Memory & Place in Black Portland bursts with culinary references. Community is partially bound by what sticks to the ribs. DeAngelo Turner’s “Doris Cafe on Russell and MLK,” features a joint where upon entry you are hit with the smell of “hot BBQ with a hint of honey” and further inside “the chatter of different cultures, of people writing or sitting inside the cafe to eat that good food.” It takes some time for the food to make its way to the table, but its arrival brings salvation.

Turner also recalls Jake’s grocery store which once thrived at 9th and Alberta. The smell and taste of “jojo’s and chicken” and “seasoned potatoes”–a value at $2 that in real numbers means a tray of “at least 10 jojo’s and 5 drumsticks” is a welcome memory, counterposed to Kay Johnston’s photograph of the corner, showing Turner “all the 31 years of absolute departure from this Portland neighborhood.”

Medero Moon remembers the Going St. Market on North Williams Avenue when it was owned by a Black man named Phat Charles who let people buy needed food on credit. He was “so much more than just a Black owner of a store. He was a pillar as well as a gatekeeper to the community. He was a provider when our families didn’t have money to give. That little corner store on Going St. connected our community in a way greater than our understanding.”

Mr. Charles no longer owns the store. Stressla Lynn Johnson remembers when it was named Maxie’s, a block from her Auntie’s house, and attended by Mr. and Mrs. Maxie. Like Moon, Johnson recollects the store as “an integral part of the community’s heartbeat.” Mrs. Maxie, she fondly recalls, always had Johnson and her friends “in her loving and caring sights” as their eyes wandered the many varieties of candy “situated in a way that was convenient for kids.”

However, in “Penny Candy…Gone Street Market (III),” Johnson writes of the change gentrification has brought to the same but markedly different place, now girded with “Black security bars” ironically implying “the distrust of strangers.”

I hear the store is not the same …

An old white lady stands behind the counter and don’t even know the smilin’ kids’

names … That she has been suspiciously watching ever since their little feet crossed

the wooden threshold …

Johnson notes that the penny candy once spread out by the Maxies for kids to pick from is gone. Much is gone, she laments, “…especially the/people that loved the Black Community.”

One of the many strengths of this collection is its pairing of narrative with poetry. In “The Park,” Johnson’s prose recalls gatherings at Peninsula Park. The sight of “majestically distributed” trees, perhaps maple or oak or pine, “standing like giant sentinels over us”. The sound of the fountain that sometimes became a swimming pool. The smell of the freshly mowed field. Family gatherings including those of “families not necessarily related by blood–always interrelated in the Essence of Black Love.” Stories and tales, the one that got away a little bigger each year. And children having fun being children, but “always under the watchful eyes of every adult in the park.”

Like most of the essays in this book, Johnson leans heavily on describing what was. But the accompanying poem, “Being In/At That Park,” gives us how it felt. The narrative is stripped to its bones.

Old friends and family that haven’t gathered since last

year.

Getting caught up on life’s changes over a nice cold

beer.

The parks of my youth: Peninsula, Unthank, Irvington, Alberta, and

Pier.

Looming large in my heart-soul’s memories of places I hold Near and

Dear.

After reading this collection it can be difficult not to feel a sense of something lost, a place that, while recognizable to its authors, may no longer recognize them. But as Bates and Imarisha note in the introduction to Memory & Place in Black Portland, “the removal from a physical location, or even its destruction, does not affect its existence.” And for all the losses lamented, this collection points forward. The gentrification of Albina has not resulted in the eradication of Portland’s Black community. In “9th and Alberta” Turner notes that it has relocated to Gresham where it has retained, according to Johnson, what it holds Near and Dear.

The PSU Black Studies students whose works appear in Memory & Place in Black Portland have taken their place in the long tradition of withstanding white supremacy by challenging its dominant narratives, and embracing the stubborn resistance of memory. From behind prison walls, their stories pulse with the life of a vibrant community, offering echoes of what McClinton enshrines as “this sacred place/A Black placemaking place.”

To view some of the entries in Memory & Place in Black Portland, go to: https://www.theponyxpress.org/s/psu-black-studies-portfolio

The author apologizes for the formatting error in the presentation of McClinton’s poem “Gentrification.”