Story and photos by Pete Shaw

In late February 2020 I went into something like a lockdown. The novel coronavirus was just making news in the United States, and since I take immunosuppressants, my better 99% and I felt it would be best if I laid low. While I had no illusions regarding how long the pandemic might last, I had hopes that it would be over, or at least that I would be able to resume something of a more normal life, sooner than later. That quickly and clearly became false optimism, but I readily tempered it with reality. I masked up whenever going out into my limited world, and I usually went out when there were few people around. That limited world was wherever my walks outdoors would take me. My better 99% did all the shopping, picking up of library materials, and whatever else outside of medical appointments required entering a public space.

I missed taking part in and writing about a lot of history. The George Floyd and wider rallies for Black lives; protests in support of immigrant rights and justice; demands for single payer covered universal health care; and anti-fascist actions–I took them in from the sidelines. It was stimulating and uplifting seeing Friends and comrades fighting good fights. And it was demoralizing that I could do little more than cheer from home.

This is not to say I was not active. I was, but in a much smaller, if still meaningful way. I made bread for people. I offered vegetables and fruits that we grew, and I made meals available when I could. Every so often I toyed with the idea of attending some important event, but my better 99%, and many Friends including those involved, urged me to consider my health. Reluctantly I did, although always with the mantra running in my mind as it has for over 20 years now, that if my better 99% thinks something is a good idea, then it is a good idea.

Last Friday, September 10, two weeks after receiving my booster shot of the Pfizer vaccine, I asked my better 99% if she thought it okay for me to attend a rally the next day in support of the striking workers at the Portland Mondelez-Nabisco plant in North Portland. She saw no problem with it so long as I wore my mask and maintained distance as best I could.

As I chugged along Northeast Columbia Boulevard, I saw the large numbers of strikers and supporters that I have seen there since the strike began on August 10. Judging from the size of the crowd, I realized parking could be a problem. And indeed, wonderfully, it was. After parking a ten minute jaunt away, I soon was part of the boisterous few hundred that had come to raise their voices in support of the striking workers.

The strike came on the heels of the May 2021 expiration of the contract between Mondelez-Nabisco and members of the Bakery, Confectionary, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers’ International Union (BCTGM). Largely due to the pandemic resulting in a greater demand for snacks, and the workers meeting that demand, Mondelez made over $3.5 billion in profits in 2020. Workers were putting in 12 hour days, seven days a week, churning out some of the products–Oreos, Chips Ahoy, and Nilla wafers to name a few–that I remember as staples of my childhood.

Enough is never enough for capitalism, and so despite these handsome profits, Mondelez–which earlier in the year closed two plants, in Fair Lawn, New Jersey and Atlanta, Georgia, resulting in the loss of nearly 1,000 jobs–is demanding that workers give something back. Actually, many things. BCTGM members have claimed that during negotiations Mondelez’s management pushed terms that would eliminate overtime by making those 12 hour days standard instead of the current 8 hours, not allow for holidays off, reduce health benefits for new hires, and make standard those weeklong 12 hour days. As the indispensable journalist Don McIntosh over at the Northwest Labor Press so eloquently put it, “If—as the bumper sticker says—the labor movement is the folks who brought you the weekend, then Mondelez-Nabisco is staking out a position as the folks who want to take the weekend away.”

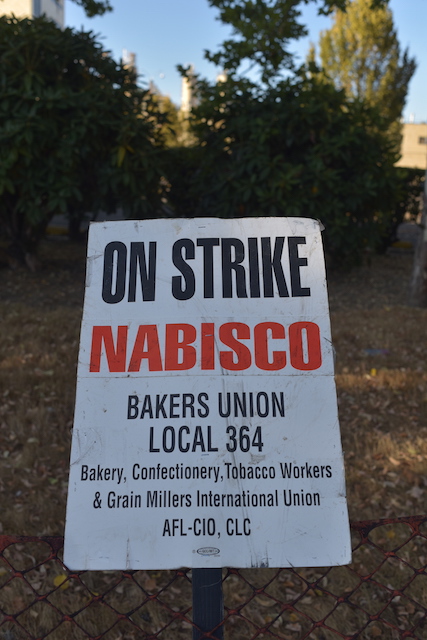

Soon after nearly 200 Portland workers of BCTGM Local 364 walked off the job, they were followed by their fellow Nabisco workers involved in the same contract negotiations at the other remaining bakeries in the US, in Chicago, Illinois and Richmond Virginia, as well as those workers at distribution plants in Addison, Illinois; Aurora, Colorado; and Norcross, Georgia. About 1,000 Mondelez-Nabisco workers are now on strike.

The union is demanding there be no changes to current scheduling and overtime systems, as well as to the current healthcare plan. It also wants Mondelez to restore its pensions which the company replaced with a 401(k) plan three years ago. As well, the union is seeking guarantees against sending jobs elsewhere, an understandable concern since Mondelez recently built a $130 million plant in Mexico.

Mondelez has responded crudely to the strike. In Portland, it has tried bringing in scab workers, with Mondelez’s hired goons at Huffmaster roughing up strikers and supporters, although it seems those scabs have not had an easy time getting into the bakery. According to many of the workers, production at the plant is down. On August 31, Mondelez rescinded health benefits for striking workers and their families. The company has numerous lawyers at its disposal doing what it can to break the back of the union. Of course, Mondelez claims they only want to bargain “in good faith with the BCTGM leadership.”

But where there is oppression, there is always resistance. Union electricians and machinists who normally would work in the plant refused to cross the picket line. Teamster truckers have declined pickups and deliveries. Union railroad workers have honored the picket line, backing up their trains when told they would be delivering ingredients that scabs would use to make Nabisco products.

Saturday’s rally, organized by the Portland branch of the Democratic Socialists of America, was attended by members of other unions including the Oregon Nurses Association, the Inland Boatman’s Union, the International Union of Operating Engineers, the Iron Workers, and the Teamsters. Other unions and organizations supporting the striking workers include Portland Jobs with Justice, Portland State University’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors, SEIU Local 49, Oregon AFSCME, and the Black Millennial Movement.

Local politicians powerfully gave their voices and backing to the striking workers.

Multnomah County Chair Deborah Kafoury emphasized the growing support for the Mondelez-Nabisco workers. “There is a clear line in the sand here,” she said. “We have on one side corporate greed and absurd demands, and on the other side we have family wages, economic justice, and people power. Our community chooses economic justice. Our community chooses the right for people to thrive.”

Lori Stegman, a Multnomah County Commissioner of Korean descent, talked about her vision of the American Dream, that people could make a living wage and be valued for their contributions to workplace and community. That vision, she expressed, now seemed illusory. “The actions of corporations like Mondolez remind me that the American Dream is outdated, and has been used to divide our country into classes with extremes of wealth and privilege. It’s actually been a nightmare for workers in our country…distorted by greed and indifference, where a lack of empathy for human rights has been distorted to power and success through the lens of capitalism.”

Andrea Valderrama, who represents outer East Portland in the Oregon House of Representatives, a district she described as “mostly BIPOC, mostly low income, and most importantly, tired of being sick and tired.” Valderrama, who is the first Peruvian-American to serve in the Oregon legislature, was visiting the strike line for her third time. Some perhaps wondered why she, whose district lay far across town, was taking the time to be there.

“You may be asking,” she said, “Why so much solidarity if this isn’t in my district? It is so important to me to continue to show up and show solidarity. I know what it’s like to feel alone. I know what it’s like to fight the impossible, the powerful, the dominant culture, the rich, the greedy. I know what it’s like to be told we won’t win. They keep trying to bury us. But they don’t know that we are here today, we are seeds in this movement. They don’t know that I’ve got your back.”

Oregon House District 28 Representative WLnsvey Campos echoed Valderrama’s words. Campos, who grew up in a working class family with her father employed in restaurants and who has worked as a day laborer, stated, “I was taught early on that the most important word in the language of Working Class is solidarity.”

This too was Campos’s third time on the Mondelez-Nabisco strike line. She noted the greater meaning of the Nabisco workers’ struggle. Campos told the crowd, “The fight today out here with the workers helps everyone. Because it’s not just about money. It’s about transformational change. Not just here and now, but for workers across the country who deserve to be treated with dignity and respect. Workers who deserve healthcare, who deserve justice, who deserve good working conditions. It is embarrassing and it is obscene that Mondelez, a corporation that has made record profits in this last year, is working to worsen pay and working conditions.”

Campos closed with a ringing reminder of the path forward, stating, “CEOs and their investors, they depend on workers. And yet through their actions, they have acted as if folks are expendable. But what they have forgotten is that no matter how much the economy seems as if it is upside down, the power lies with the people. The power lies with the working class. And it is the solidarity of our actions that is going to get us through. It is standing together. It is through a collective struggle together, because workplace rights are human rights.”

Following those politicians, a series of Mondelez-Nabisco workers spoke. Every one of them was the embodiment of this and all workers’ struggles, and each had their own story, each a unique thread in the working class quilt. Some had been working for many years–more than 45–while others had put in only a few years on the job. If their words were not as soaring as those of Campos, Kafoury, Stegman, and Valderrama, they were equally stirring both in terms of the immediate time and place, and the wider meaning.

When Shri Mudalier thanked the owner of Toast for consistently feeding people on the strike line, his gratitude was for presence as well as food. “It’s not the thing that he brings,” said Mudalier. “It’s the thing that he puts in.”

As so many people who were there Saturday understood, and as Mike, the Vice-President of the union put it, “This isn’t a workers’ strike. It’s a people’s strike.”

Mudalier, and later Jesus Martinez, president of the union, made note to thank Brian, an IUOE engineer who works in the plant. Earlier, he and six of his union brethren went to cross the picket line. When the strikers tried appealing to their better angels, only Brian heard their voices. It was a brave show of solidarity, and he was rightly recognized for declaring which side he was on.

As well, during the rally, it was announced that the workers’ strike fund had exceeded $80,000 in donations.

As community support grows for the striking workers at Mondelez-Nabisco, the building of the plant in Mexico is another reminder that labor must think bigger. As capital becomes more globalized, labor too must organize across borders. The Portland plant workers seem much of the way there, noting their fight is not with their fellow workers in Mexico who will be baking Nabisco goods, but with Mondelez International. Martinez noted how the union created a video of support for “our brothers and sisters in Argentina and Venezuela.”

Workers in Mondelez-Nabisco plants in those countries too are being squeezed for wages and benefits. According to a video sent by Venezuelan BCTGM union president Victor Gutierrez, workers at those plants do not make enough money to support their families.

Martinez also expressed hope that they would be able to reach “our brothers and sisters in Peru and Mexico” in their struggles.

But even then, it is important to note that the struggle against Mondelez, important as it is, is just a struggle against a small piece of the machinery of capitalism. To play with an observation by John Dewey, Mondelez is but part of the shadow cast by capitalism, and changing the shadow does not change the substance.

That fight, of course, is not only the fight of these brave and boisterous striking workers. It belongs to all of us, something that was made clear on Saturday with all those different spokes of labor and community members giving their support to their fellow workers who for over a month have been marching along Northeast Columbia Highway, demanding their innate human dignity be respected.

This is what solidarity looks like. I had not forgotten what it was. But only when immersed within this righteous crowd did I remember just how beautiful it is, and how much I had missed it.