Story by Pete Shaw

The late Joan Didion once wrote, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” While I agree with the general tone of that statement, there are always exceptions to even the most beautiful of rules.

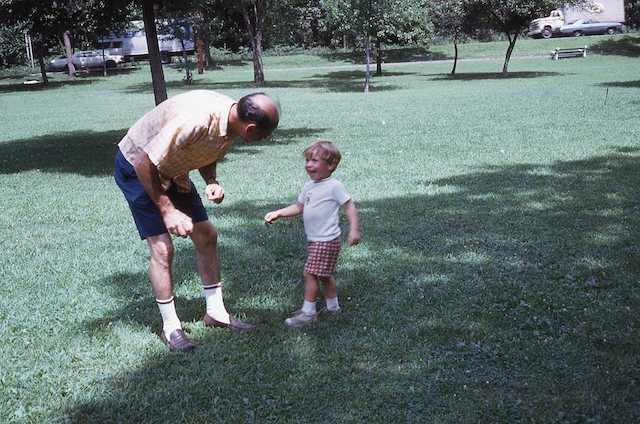

When I was a kid, my dad told me many stories. As he was a scientist, those tales were firmly grounded in reality, often told because he felt there were things I should know.

Take hemophilia. Perhaps because he read something about it in the newspaper–he read the news section of the New York Times nearly every day–he thought I should know about the disease. Not long after, my mom got a call from Miss Watson, my kindergarten teacher. She was worried about me. I had stopped engaging in play at recess, preferring either to sit at my desk or stay away from the other kids when outside, worried about catching hemophilia, getting a cut, and bleeding out.

My father had neglected to mention that I could not catch hemophilia. This resulted in my mom and he having, as the fellas say, a Talk.

Not long after that incident, my dad decided I should learn some history. At some point, I think prior to my birth, a passenger train had been leaving New York City, heading west over the Hudson River. It was a foggy night, and the conductor did not know that the bridge ahead was up. While his application of the brakes saved a complete disaster, quite a few cars were left hanging over the edge of the deck. The people in those overhanging cars, desperate to get out, pulled themselves over each other and up what once were floors.

This was what my father deemed a fine bedtime story. Another Talk followed. There were surely many more Talks because there were many more things my father thought I should know.

That was a fun story.

Here is a good one that I recently told to some close Friends.

Back in July of 1998, I was readying to move to Chicago to live with my better 99%. The night before splitting New Jersey my dad took me to pick up the moving truck, a smallish Hertz item, and a trailer which would haul my car. All my nerves were vibrating positive.

We got the truck back to the house and I began loading up. It was late by the time I finished and opened a beer. My dad, past his usual bedtime, came out. He wanted to talk.

My dad had always been a bit hands off with me. I often joke to people that he gave me only one rule: Don’t call me from jail. There is some truth to that, although hardly in entirety. If nothing else, when I got arrested for committing an act of civil disobedience and spent about seven hours in a holding pen, he was proud of me. But he gave me little more than good guidance in life. Orders were rare, perhaps because he realized early on that I was the type who chafed at orders. But if you give me guidance with a teaspoon of sugar, I’ll eat it all day.

So there I was in the garage, leaning on his car. We talked about my plans. He talked about how wonderful a person Jessica was. I agreed and added on. I sensed there was something else on his mind.

“You’ve clearly got something to say, dad. Shit it out.”

“What are you going to do if this doesn’t work out?”

My dad is a practical man. This is not to say that practicality governs his life, but being a scientist his mindset leans that way. And besides, I am his son, and he was understandably concerned.

If Jessica and I did not work out, where would I go? What would I do? Where would life take me? Overall: how would I respond?

That night, he was not looking for a practical answer. He wanted a Right answer. And as far as I could tell, I gave it.

“I’m in Love, dad. I have to do this. And if it doesn’t work–and I don’t see how it will not–then I move along.”

He replied as he replied to so many things that pleased him. “Good!”

And so it was, and so it is. Jessica Loves my dad, and my dad Loves her. As well, they also like each other immensely. They take obvious pleasure in each other’s company. And we all enjoy the company of each other.

My father is not far from 97 years old. Every time I saw him over the past ten or so years, I left pondering heavily that I might not see him again. Almost nothing has been left unsaid, and that which was, I had determined irrelevant, which is to say, a waste of limited valuable time. When The Virus struck, I was quite sure I would never see him again. This has turned out to be true.

My father went into hospice the other day. He may be dead by the time you read this. The morphine is running. So is time, toward a finish line that while a bit hazy, is now visible in the very near distance. Two days ago my brother called me and then told my father, who was in one of his rare awakened moments over the past month, that Jessica and I were on the phone. We talked to him, both monologuing as my father was unable to respond. My brother said he clearly perked up when told it was us.

Yesterday, apparently because the morphine relaxed some muscles associated with drinking, he had his first real drink of water in a long while. He said hello to me, the standard, “Hi, Peter,” in what my brain registered as the same way he always has. And he concluded with the same words he always has: I Love you, Peter. Bye.

A few minutes ago, my brother sent me an email. Our dad is resting comfortably. My brother would like me to gather a list of the names of our father’s siblings. There were eight of them. He is the last one still living.

I find myself in a melancholic reverie, thinking of my dad. Images and sounds cascade. Stories give rise to more stories, reminding me of a Good person–not a perfect one, but a Good one–with whom I was lucky enough to share some time in this life.

I Love you, dad. It was Fun. Thank you, and goodbye.