Story by Pete Shaw

Nine years ago, near the corner of NE 6th and Halsey, Keaton Otis was murdered in a hail of 23 bullets fired by a clutch of police officers of the Portland police’s Hot Spot Enforcement Team. In video capturing the event, it appears to be an execution. Otis had been profiled by the police, and Officer Ryan Foote later stated he pulled Otis over because “He was wearing a hoodie…He kind of looks like he could be a gangster.” The police said Otis had fired first, although none of the six officers involved in his murder said he had a gun, except for one who later admitted he did not see a gun. No gun has ever been produced as evidence in the case.

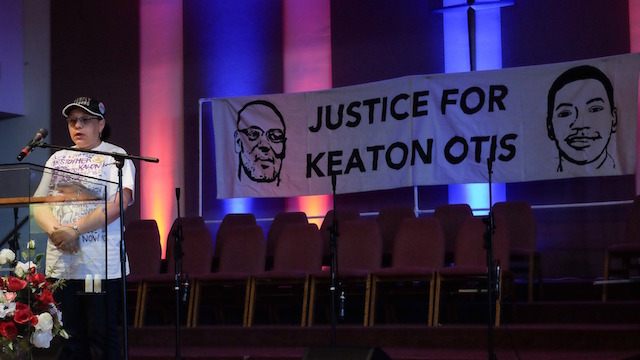

Two months after Otis’s murder, his father, Fred Bryant, began holding a monthly vigil on that corner. After Bryant passed, when those bullets eventually took his life two years after taking his son’s, the vigils continued. On May 12 at Maranatha Church in Northeast Portland, over 75 people gathered to remember the lives of Keaton Otis, his father Fred Bryant, and all victims of police violence. The yearly anniversary of Otis’s murder is often held in a house of worship, most often Maranatha Church, but sometimes Augustana Lutheran. The anniversary has become both a remembrance of those who have been murdered by police and also a time to recommit to seeking justice.

Those memorials exemplify the politics of hope and give the community an opportunity each year to recommit to organizing for justice. This is why, on the 12th of every month, people come together to remember Otis, Bryant, and all others gunned down by police: not just to keep their memories alive, but to express the hope–the rock steady belief–that one day police shootings of Black people and those experiencing mental health crises will stop. The memorials stand against the culture of modern policing that upholds capitalism and regards the bodies of Black people and those suffering mental illness as little more than detritus.

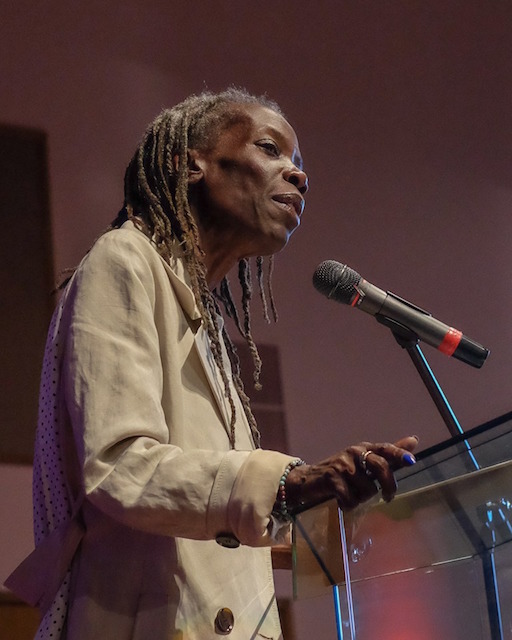

This year’s memorial coincided with Mother’s Day, both of which emcee Walidah Imarisha noted were events that honored love and commitment. Imarisha observed that the police who murdered Otis were “criminalizing blackness and profiling him” and added that it was “so unfortunate and heartbreaking that we have to add more names every year.”

The beauty in lamentation lies in recognizing movement along that arc of history toward greater justice. Julie Perini and Erin Yanke, who along with Jodi Darby produced the powerful documentary Arresting Power, presented portions of their interview with Fred Bryant that were not used in the film. Nearly six years after his death, there he was, vulnerable and beautiful, a parent whose worst nightmare had come true, grieving his son and confronting the system that killed him. In one portion, Bryant talked about how he found out his son had been killed. He saw on the news that the police had shot and murdered a young Black man in the Lloyd District, and he said of the bullets police fired, “I felt every one of them.” Eventually, two days later, Bryant found out it was his son who had been killed. The police did not contact him. He found out while watching the news.

When Bryant went down to the police station, the District Attorney told Bryant his son’s murder was justified. Bryant would spend the rest of his life seeking justice for his son, noting that “the City will protect these officers at all costs.” Indeed, none of the six involved officers has been held accountable for murdering Otis. The DA told Bryant that Otis had shot at the officers, yet no evidence of that has ever been produced. When Bryant asked if the gun that Otis purportedly shot was checked for fingerprints and residue, the DA responded that only in Hollywood were such investigations performed.

Bryant’s living timeline ended on October 29, 2013. Irene Kalonji’s 19-year-old Black son Christopher was murdered by Clackamas County sheriffs on January 28, 2016 while struggling with mental health issues. Kalonji continues fighting for justice on his behalf. She thanked Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty, who brought her to one of the Keaton Otis vigils where she has since been a regular presence. She said Hardesty told her, “You can do it. You can fight for Christopher, and we will fight with you..” Kalonji also noted that Bryant was an example to her and others who have lost loved ones to police violence.

Joe “Bean” Keller’s son Deontae was also murdered by the Portland police. Keller was not only friends with Bryant, but also knew the parents of Kendra James and James Jahar Perez. Keller described the feeling of losing his son as “overwhelming” and “overbearing.” After Keller spoke, he played a video of a song he wrote. The song, “Before There Was Trayvon,” is a stark reminder that there are some wounds that time can never heal. The song also encapsulates the overarching theme of the night: endurance. Art, like memory, lives on, and each can give meaning to the other.

Keller’s fight for justice for Deontae is in its twenty-third year, which is older than the three young Black Lives Matter activists who next took to Maranatha’s altar. One read a poem by Antwon Rose that includes the lines, “I see mothers bury their sons/I want my mom to never feel that pain.” Antwon Rose was killed by police in Pittsburgh the year after he wrote the poem.

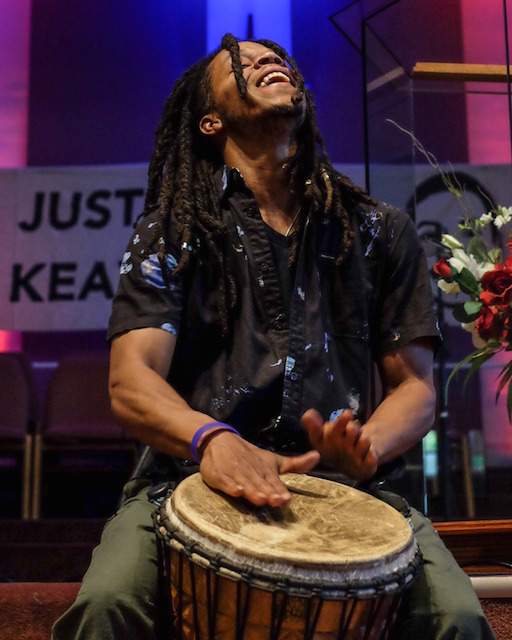

Jamaali Roberts played a djembe, an African drum, with an emotion that summoned spirits long gone, and called out to those who are still engaged in the struggle for justice.

Imarisha is a poet, and she gathered many of the feelings that had been set loose when she stated, “We have lost parents. We have lost children. We have lost irreplaceable brilliance.” But we have not lost their stories. Maria Cahill of Pacific Northwest Family Circle told the crowd that despite the City and the Portland police wanting “to sweep this story under the rug,” a campaign is afoot to establish a permanent memorial at the corner of NE 6th and Halsey. She noted that Keaton Otis, like so many other victims of police violence, was targeted because he was Black, and our resistance to police violence and all forms of racism must be rooted in that truth.

Francis Fabian, a young Black man who had a close friendship with Otis for 18 years, spoke in glowing tones of his departed friend. Otis, he said, was 6’ 5” and eschewed basketball for baseball. A humble friend, quiet as a monk. A good person and a good influence. A guidepost in life as well as in death, for good and a reminder, “There is nothing to keep me, my family, and my friends from becoming the next Keaton Otis.”

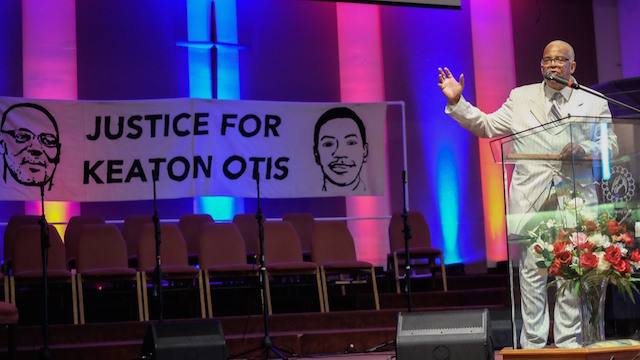

The evening was rounded out by Commissioner Hardesty and Reverend Dr. Leroy Haynes. Hardesty brought the passion and commitment that has made her such a refreshing presence on the City Council. Mentioning how Haynes had told her “the arc of justice is not for the weak of heart” and that “it is not for those who want quick solutions,” she told the audience, “No one ever gets justice because it’s fair and appropriate. The only way you get justice is you have to fight for it.”

On the council she has been fighting for it, working to reign in the police, much to the annoyance of Mayor Wheeler, whose budget is full of the usual distribution of largesse to the Portland Police Bureau (PPB). That budget calls for money to be spent experimenting with body cameras that Hardesty says the City cannot afford. Hardesty wants to disband the former Gang Enforcement Unit, now rebranded the Gang Enforcement Team, but regardless of name, a group of police who as Portland Copwatch’s Dan Handelman had earlier noted, stop and search a far higher percentage of Black people than are represented in the city’s population. “A budget is a moral document,” she said, and it “should be protecting people.”

“Maybe, just maybe,” said Hardesty, “we can take $2.5 million out of the police budget, and nothing will happen.”

She encouraged people to get more involved in pushing for a budget that reflects the morality that brought them together that night in the fight for justice and to not give into despair. “When people say to me, ‘I’m only one person,’ I say to them, ‘I give you exhibit A, Fred Bryant.” Before his son died, Hardesty said, Bryant had never testified before the City Council or wrote a speech. But he never let his quest for justice for his son stop him from taking those actions. Nine years after Otis’s death, she said, we were in Maranatha Church because Fred Bryant decided that no matter what, he was going to stand on the corner of NE 6th and Halsey on the 12th of every month.

Fighting for justice has taken up the majority of Dr. Reverend Haynes’s life. His fiery speech was vintage Haynes, a stalwart and beautiful combination of the demand for justice with the conviction that it will one day be gained. Haynes is a living example of what he encourages: to keep pushing when it seems you are getting nowhere. The arc of history is bent toward justice by those who push for it consistently.

Back in February, Police Chief Danielle Outlaw held what was billed as a listening session at Maranatha Church in Northeast Portland. The event, also attended by Mayor Ted Wheeler and a coterie of Outlaw’s upper brass, was held in response to the news first reported in the Portland Mercury and Willamette Week that Portland Police Lieutenant Jeff Niiya had been exchanging cordial text messages with Joey Gibson, the leader of the Washington State-based white supremacist group Patriot Prayer. Those texts buttressed what had become obvious to members of the Portland anti-fascist community, namely that the Portland police have often acted in the service of Patriot Prayer and the affiliated white supremacist groups that attended its rallies.

The affair was a fiasco. Much of the time was spent listening to white supremacists and their apologists–the very people with whom Niiya had been making nice, and Outlaw and Wheeler did nothing about it. It seemed a cynical display at the time, and three months down the road, it only feels more so. Wheeler has produced a budget that fetes the police with more money, and he has not taken kindly to Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty questioning what she and others consider wasteful spending. That late February night in Maranatha Church appears to have been little more than a poorly-organized, hastily-called venting of community steam, something far short of an event where Outlaw and Wheeler actually listened. Instead they appeared to be counting down the minutes before they could go home and get some sleep.

When I left Maranatha Church on that late February night, I felt nothing short of disdain for Wheeler and Outlaw. They were there because they had to be there. They were not there to listen. They were there to appear as if they were listening. Their ambitions do not include justice, and their ambitions would only include justice if it would advance their career prospects.

But on this early May night as I again left the temple, I felt only the buoyant light that I have come to know on many occasions from being in the presence of people who against seemingly insurmountable odds fight for a better, more just world.

It is worth fighting for.