Story and photos by Pete Shaw

Always bring a crowd.

In many cases, that is sound advice. A month ago, when Francisco Aguirre was checking in at the administrative offices of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency (ICE) which are located in the ICE prison on SW Macadam, two people accompanied him to his appointment. Aguirre, who currently possesses a work visa, must periodically appear before immigration officials at the ICE prison to show he is following the various requirements of his visa.

Four years ago Aguirre made news when he took sanctuary in Augustana Lutheran Church after ICE agents showed up at his home and attempted to arrest him in September, 2014. Aguirre resisted, and he soon found himself at the house of worship located in the Irvington neighborhood in Northeast Portland. He remained there for 81 days as the US government continued threatening to detain and deport him. The nearly quarter-year Aguirre spent in Augustana Lutheran occurred against the backdrop of the Department of Justice pursuing him for nearly 21 months on an illegal re-entry charge that was finally dropped in May, 2016.

It was a victory not only for Aguirre, but for the immigrant rights and immigrant justice community. His case helped shine a light on the many obstacles faced by migrants to the US, particularly those from Central and South America, and Mexico. Aguirre came to the US from El Salvador in 1995, fleeing violence that was largely the consequence of US foreign and economic policies, particularly the Dirty Wars in the 1980s and the Drug War. Those US interventions resulted in destabilized legitimate governments, and in the many places where those governments had no power, their rule was replaced by that of drug cartels and other groups using violence to achieve their ends. This combination of instability and the gang violence that came with it continues compelling people to leave their homes, refugees from the extreme duress they did not ask for.

While the US is quite willing to craft and impose the policies compelling people to leave their homes, it has proved predictably averse to welcoming those same people as refugees, something which it is required to do by international law. And if the US was flagrant in overlooking the foreseeable violent results of its policies, it was equally shameless in ignoring its obligations toward those seeking refuge from those likely outcomes.

A recent ICE report showed that while deportations are on the rise under Trump–over 256,000 in fiscal year 2018–that number still does not scratch the 2012 pinnacle during the Obama Administration when 409,849 people were deported. During his last two years in office, Obama oversaw fewer deportations, although those numbers were only slightly less than Trump’s, about 235,000 in 2015 and a little over 240,00 in 2016.

While that dynamic on the part of the US remains relatively static, the election of Republican Donald Trump to the presidency has seen him ramping up steeply the number of arrests of immigrants without serious criminal convictions. Over 80,000 of the 158,581 people without documentation arrested in fiscal year 2018 had been charged or convicted of driving under the influence. The next two highest categories were crimes involving “dangerous drugs” and traffic offenses.

The rhetoric surrounding these arrests has long centered on these people’s violent criminality, but a table included in the ICE report shows that of those ICE arrested, only about 40,000 would be classified as violent offenders.

Many of the arrests have been warrantless, with ICE agents racially profiling immigrant communities composed of people from Mexico, and Central and South America. Those arrests have occurred in workplaces as well as immigration offices and courthouses. Furthermore, the level of cruelty in ICE’s arrests, as well as in the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) detentions and separations of families seeking asylum along the Mexico-US border, has somehow been ramped up. Both ICE and the CBP are under the jurisdiction of the Department of Homeland Security.

Trump’s approach has certainly been more flagrant than that of presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush, with families, often torn apart, being housed in tent city-jails. In June, San Diego, California US District Judge Jane Sabraw issued a preliminary injunction ordering the government to reunite separated families. Over 145 days later, 173 children snatched from their families at the Mexico-US border remain in US custody, still separated from their families. Meanwhile, the number of children imprisoned in over 100 federally contracted jails across the country is approaching 15,000.

Some results have been even more horrific, including the recent death while of seven year old Jakelin Ameí Rosmery Caal Maquin while in CBP custody. Adding insult to injury, the Trump Administration blamed Caal’s father for her death. Caal and her father were fleeing from Guatemala, where the US has a long history of usurping democratically elected governments in favor of brutal regimes that uphold US economic interests.

But if times seem grim, Aguirre bears them with a smile. In November, when heading to his appointment, he grinned at the two people who met him. But it was clear he was nervous. So were the many other people entering the ICE prison’s administrative area. Their uneasiness was understandable as ICE agents have been swooping in and arresting people without documentation when they show up to these required meetings.

A few years ago, Aguirre had been applying for a U-Visa. It is a special status available to immigrants who are victims of serious crimes, as Aguirre was in El Salvador, and who have cooperated with authorities in prosecuting those transgressions. Despite him meeting the requirements for obtaining a U-Visa, as well as the fact that his life would be in danger were he to return to El Salvador, Aguirre’s petition was denied in 2015. He then obtained a work visa which expires in 2020.

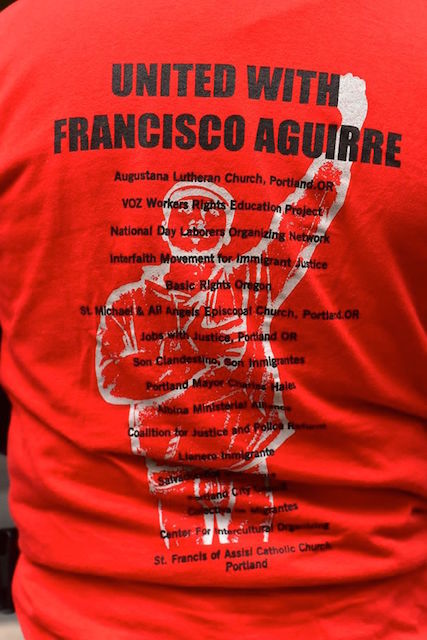

The two people who met Aguirre just prior to his November check-in were an anomaly. Usually, he is accompanied by a large number of friends and supporters drawn from a wide swathe of the immigrant rights and immigrant justice communities. Despite ICE’s augmented audacity under the Trump Administration, those people make a difference.

Aguirre’s November appointment took approximately an hour, and he was not allowed accompaniment. Prior to entering, he and one of the people with him arranged to keep in touch with text messages, optimally every 10 to 15 minutes. Twenty minutes after he passed through the security checkpoint and out of sight, no text message had been received, and there was more than a slight hint of worry among those outside. But soon he sent word that he was being delayed, and subsequent messages were mundane. When Aguirre left the building, there was a palpable sense of relief, but also a bit of a somber tone.

During his check-in, Aguirre said the officer dealing with his case originally gave him paperwork that said his next appointment would be on November 18, 2019. Aguirre said the officer then asked him if he was “the one hiding at a church,” to which Aguirre replied, “I was not hiding, but defending my rights and freedom that I deserve like any human being.”

Then, Aguirre said, the officer requested back Aguirre’s documents and left, likely to consult with his higher-ups. “When he returned with the paperwork,” said Aguirre, “I saw that he changed my check-in date to December 12, 2018, and he said I will be doing my check-in every month.”

“I asked why he was doing that,” Aguirre continued, “and he replied, ‘Have a nice day, Mister Justice. You will be reporting every month now.’”

Aguirre stated this was not the first time they had spoken to him pejoratively. On another occasion, he said an officer laughingly told him, “I hope to see you on a big kaboom.” The comment confused Aguirre, but the other people checking in at the time told him they thought it meant wanting to see Aguirre a victim of a bomb explosion.

When asked why he felt ICE was treating him this way, Aguirre responded, “They are just trying to make it harder for me. They just don’t like that I do whatever I can to defend myself when they try to go against my rights and the rest of the immigrant community. ICE, like any other police agency, uses the same tactic to harass people. They do it when they see there is no noise around that individual. They wait until they see that we are not getting the community behind us. When they see that people are with us and watching their actions, they tend to do better and avoid getting caught doing the wrong thing.”

Yes they do. This month’s meeting, at 10 AM on December 12, had a different feeling to it. Over 30 people showed up, many of them from the First Unitarian Church’s Immigrant Justice Action Group. Prior to making their way with Aguirre toward the prison, Pastor Mark Knutson of Augustana Lutheran Church offered a prayer favoring immigrant justice, as well as justice for Aguirre.

When Aguirre was met this time at the entrance to the ICE prison, backed by this large crowd, he was allowed in along with two other people. Twenty minutes later, they emerged from the building with good news: Aguirre’s next appointment would not be next month, but rather, in March.

Outside the prison, Aguirre expressed his gratitude to the people who had shown up to advocate for him. “You are the change, the power of justice,” he told them. “When the power of the people stands up, there’s no way or nothing that can be stopped. Every time you as a people stand bymy side to provide support, you give me the strength and energy to continue resisting until I reach the freedom I always dream of.”

That power, Aguirre realizes, is not just about supporting him, but all immigrants seeking justice. “When an immigrant shouts to the people, asking for help,” he said, “it is not only the individual cry, but the cry of the entire immigrant community asking for a helping hand. And when the people provide that friendly hand to our people, it is like an injection that can eliminate the disease of fear. It is the most powerful tool or key to paralyze the oppressor who tries to intimidate our immigrant people.”