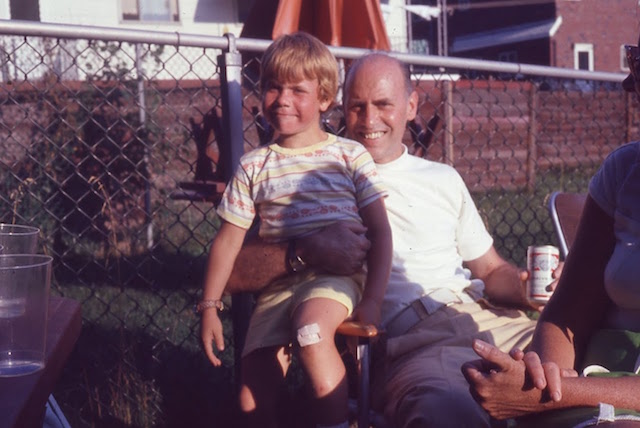

Photo by Marilyn Shaw.

Story by Pete Shaw

“See my friends playing across the river”

–Ray Davies

Spend any reasonably lengthy amount of time with me, and you will come to know in deep detail how much I love the music of The Kinks. Music is the art through which I best interpret and understand this world and my place in it, and much of that band’s catalogue, composed largely by its singular frontman Ray Davies, has provided a wondrous and wonderful, if often melancholy, soundtrack to my life. Like any art worth its salt, their songs both inform and guide me.

Around 1997 I went to see one of Davies’ “Storyteller” shows in which he and guitarist Pete Mathison wove songs intermingling with passages from Davies’ unauthorized autobiography, X-Ray. My dad came with me. At the time, he was nearly 75, almost 20 years older than Davies. A rocker, my dad never was. Music was not really his thing, although he seemed to enjoy singing. It was a reality that sometimes made itself painfully obvious.

A couple of years earlier, my dad went with Friend Ray and I to a Princeton University men’s basketball game. At the time they were an excellent team that occasionally made some noise with the Ivy League champion’s automatic bid to the NCAA basketball tournament. The Jadwin Gym was near capacity, and we found ourselves in a crowded section of the upper deck. Prior to tip off, the US national anthem was played, and as he always did, my dad stood at attention and sang along with the music.

The man, bless him, is tone dead. For everyone around us–and I do mean everyone, for while my dad rarely hits a note, he misses at great volume–he must have seemed like some hideous reincarnation of Andy Kaufman. Well, eventually they came to that conclusion.

First they had to deal with Ray and I, because whatever it was that was coming from his mouth was secondary to those two punks who came with him. Those two rotten and irreverent bastards who, while this proud patriot was showing the proper decency and respect the crowd expected, were bent over, convulsing with laughter. Perhaps, after the song, they would be taken outside and given a lesson in respect.

But, now that they listened a bit, well, it was kind of funny. And Ray and I, only a few seconds earlier on the receiving end of many a stink eye, maybe had a point. Was it possible that every note the man sang was a minor second, the putative most dissonant of intervals between root and harmony? My father’s near palpable devotion to flag and country, combined with his horrible singing, doubtless made people wonder in what strange lamb’s blood he had bathed. Soon, the whole section followed Ray’s and my lead, some wiping tears from their faces.

Photographer Unknown

So, yes, even while my dad enjoys singing, music is not his thing. Good for him. And good for me, too. After all, when I was a child, he sometimes sang me to sleep. And I assure you, nightmares were few and far between.

For reasons that will likely never be clear, my dad took a liking to The Kinks. I educated him properly, and on a couple of occasions he asked me to “put on that Village Green” album. The child had become the father, and a proud one at that.

And so on that night 21 years ago, I led him to the Westbeth Theater, located in the West Village, Manhattan. It is a small place, with capacity for only a few hundred people. It’s intimate. We were seated about five feet from the stage.

The show began with Davies, alone with his acoustic guitar, warming us up, doing some of his more famous songs and coaxing the crowd to sing along. Putting the fan in fanatic, we all knew our parts and responded as a congregation. Now properly primed–for we would be called upon time and again to more obscure passages of lesser-known works (and each time we rose to the occasion as only the obsessed can)–the show truly began.

Davies is a prickly sort, and at least through his songs, not a person comfortable with modernity. So it made some sense that he would begin his show in the late 19th century, during the reign of Queen Victoria, and just about every person in the assembly prepared themselves for the simple call and response of “Victoria,” requiring us to sing the refrain, consisting of four slightly differently cadenced forms of her name.

My dad knew the song, and when it was time for our part, he let the world know it. He was loud, and of course, he was far from key. After two Victorias, Davies shot a nasty look at my dad, and for a moment it looked like he was going to stop the show and curse him out for heckling him. But then it seemed he realized that this man–this fan–was significantly older than him, and taking in a helpless shrug of my shoulders and mock-grimaced shake of my head, he broke into a wide smile and got back to work.

I have seen about five music shows that I would describe as transformative, and that show was one of them. It was the finest of services, and at the end, we all said, “Amen.” And it was extra special that I got to share it with my dad. It is a fond memory.

***************

Not so long ago, I got in touch with my old Friend Suzanne. We met in first grade, and during that year we were reading partners. A little advanced, we often ventured to Mrs. Wortley’s second grade classroom and made use of her SRA Reading Laboratory. The last time I would have seen Suzanne was in June 1984, when we graduated from middle school. We went to separate high schools, and as is the way of things, along our separate paths. But as is also the way of things, sometimes once-divergent paths cross.

When I visited my father, and my brother and his family, in late June, I got to see Suzanne. She lives near where we grew up in central New Jersey. Much of the way to her home from the northern part of the state where my dad and brother live is familiar. There is some comfort in these roads that at earlier times led to my grandparents and later, to Home.

First grade. I am seated in the second row, second from right. Suzanne is to my right.

To my left, as I cross the Raritan River, stretches the Victory Bridge, connecting Perth Amboy with Sayreville. It is a relatively new structure that replaced an older one, as is the span from which I view it, the Ellis S. Vieser Memorial Bridge. The original Victory Bridge was a swing type, and when I was younger, seeing it open to let through river traffic was, for a time, a treat.

It also reminds me of our neighbors when I was growing up, Mali and Kris. They were from India, moving in when I was 6 or 7 years old. They had a son Raj who was about three years younger than me. They were Kind people, and I recall my folks getting along well with them. When I was about 10, they moved across town. Something went wrong, and Kris leapt to his death from the Victory Bridge. Exactly one year later, Mali made the same jump with the same result. I do not know what became of Raj. Since Mali and Kris died, every time I have crossed the Raritan River, I have thought of them. I have wondered what might have been.

With my better 99% holding it down in Portland, I feel unmoored. I need an anchor, or even a port. A place of sanctuary.

Soon I am at Suzanne’s, arriving not long after 11:00 AM. She has plans for us. The town is small but nice, she tells me, and it has New Jersey’s highest rated diner. In a state famous for its diners–Long live The Golden Bell! Long live Yousouff’s!–this is quite an achievement, even if Suzanne insinuates that there was rampant ballot box stuffing. Once the town inspector comes by to make sure her newly installed furnace is up to code, she will show me around, and we can grab a bite. He will be here by 2:00. Suzanne is also awaiting some phone calls surrounding her job, and so we sit in the kitchen, telling stories and making plans.

At 3:00 the inspector shows, and he is gone before I return from taking a piss. Suzanne apologizes for the long wait, but I am as happy as can be. After 34 years, with our noses neither Roman nor Pug, I feel as if I have just left the Brookdale Community College gymnasium with my 8th grade diploma and run into Suzanne as we ready for our last summer before high school. The conversation is familiar. It comes easy. When the inspector arrives, I feel as if I had knocked only 20 minutes earlier. Time has fallen away. Old faces have new stories that somehow seamlessly connect past with present. Still reading partners, we now translate our lives using a vocabulary born from a common place and time fundamental to both of us. Our own lexicon, dusted off. A language of a long-ago Home once shared.

Pressed for time, Suzanne gives me a quick tour of the town. Soon, I must leave. Cribbing a line from Bernard Vonnegut, I say to Suzanne, “If this isn’t nice, what is?” She agrees, and we make plans to meet again.

I drive back across the Raritan River, this time on the Thomas Alva Edison Memorial Bridge, but more peacefully than I did earlier. My old Friend is my new Friend.

***************

A few months ago I was talking with my dad. I mentioned the Davies show. He could not remember it. My father has Alzheimer’s Disease, and his memories are fading. He is 93, so this is not entirely unexpected.

Photo by Pete Shaw

My father’s short term memory is quite poor. I repeat things for him, often, and then I repeat them again. He repeats himself, and he repeats me. While visiting, I went with him and my brother on one of their frequent trips to a nearby bookstore. I was given the honor of choosing what he would read. My father was born in Brooklyn, New York, and in the spirit of the local boy doing good, I brought forth a book on the great Dodgers pitcher, Sandy Koufax. Later, as we drove back to town, my brother asked him how he liked the book. He said he enjoyed it. When my brother asked him what he had read about Koufax, he did not know. But as he was reading it, he was pleased.

He is to a large degree, as my brother says, living in the moment. Perhaps Enlightenment is the capacity to sing eternally the minor second, knowing to your core that your key is True and everyone else needs to expand their minds.

It does not bother me that he forgets that night which meant so much to me and still brings a smile to my spirit. I got to share with him an artist whose work has greatly impacted my life and has helped me find my way through this mixed-up, muddled-up, shook-up world, much as my father has in more bedrock fashions. It was by any measure, religious or secular, a blessing.

If he lives long enough, I suppose my dad will forget me, my brother, my mom, his siblings, his parents, and perhaps, himself. This too does not bother me, although I am sad seeing this progression.

And I imagine, if I live long enough, I too may lose these things.

I have a photo my dad took while I was in Miss Van Dagna’s first grade class. It is Halloween, and soon we are going to get ready for the school parade. My mom is helping some child with her costume. I’m just to their side. Further toward the back of the photo is Suzanne. One day when I look at this photo, I may not recognize her. I may not see my mother. And I may not know the person who took the photo.

It is, sometimes, the way of things. For the moment, the losses near the end appear a small cost.