Story and photos by Pete Shaw

Time was not so long ago when a hand-delivered letter meant something. For the composer of the missive, whether something as beautiful as handwritten lines expressing tender and missed love or more mundane items such as a business letter, it showed the importance of what lay within the envelope. The recipient as well understood that the contents inside were matters of great weight that needed, and deserved, the assurance of personal service.

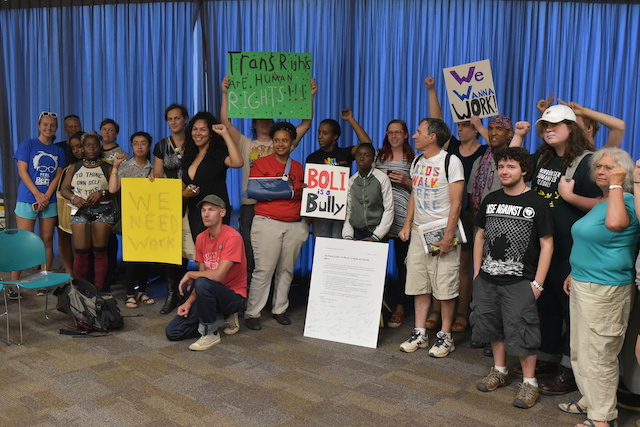

Yet when a group of over 20 transgender people and transgender rights activists tried to personally deliver a letter to Oregon Commissioner of Labor and Industries Brad Avakian on August 17, they found resistance. They sought out Avakian at the offices the Bureau of Labor and Industries (BOLI) on the 10th floor of the Oregon Building in the Lloyd District. Their letter laid out the steps transgender people insisted BOLI take to enact protections for transgender people and facilitate ending employment discrimination against them. Among the demands were that BOLI ensure equal treatment in hiring, retention and promotion for transgender workers through stepped up enforcement of anti-discrimination law; hire specialists in transgender oppression, employment discrimination, and protection; establish a training and placement program to secure employment for transgender workers; and establish a training program for employers on transgender oppression, discrimination, and protection.

The 2015 US Transgender Survey makes clear why these demands must be met. The results of the survey, which examined the experiences of 27,715 transgender respondents from all 50 states, Washington, DC, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and US military bases overseas painted a grim picture of the hardships and challenges faced by transgender people. As it relates to the workplace, in the year prior to completion of the survey, 30% of respondents who had a job reported being “fired, denied a promotion, or experiencing some other form of mistreatment in the workplace due to their gender identity or expression, such as being verbally harassed or physically and sexually assaulted at work.”

As well, there was a 15% unemployment rate among respondents, a number three times higher than the unemployment rate in the US in 2015. Doubtlessly related, the survey showed 29% of respondents living in poverty–over twice as much as the US population–and 30% of respondents reported they had been houseless at some point in their lives. Twelve percent reported being houseless in the year prior to the survey because they were transgender.

It would be unfair to say BOLI has completely ignored the needs of transgender workers. While over half the states in the country allow people to be fired because they are transgender, the Oregon Equality act prohibits employment discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

BOLI is considered a progressive office in a progressive state. At a rally prior to the delivery of their letter of demands, Charlie Burr, BOLI’s Communications Director, declared, “Any person who faces discrimination can file with our agency. We enforce the Equality Act. We strongly believe in the Equality Act. We have taken Equality Act complaints in the past. We have investigated transgender discrimination. We have investigated transgender discrimination cases. We have prosecuted those cases. We have worked on transgender training for employers to prevent issues from happening in the first place. But it’s a very serious issue. We care about it. We will continue to enforce it.”

While few in the crowd disputed Burr’s assessment, nobody was pleased with what Burr left unsaid, namely that BOLI is taking a passive role, relying on people to file reports rather than pursuing a more active one that would provide the protections transgender workers need. Alyssa Pagan, who last year moved from Portland but was in town and attended the event, noted, “You cannot expect trans people who are being degraded every day of their lives, who are being forced to live in shame to come to you–to come and get you to advocate for them. I’m sorry, but we are exhausted. The world beats us down every day and tells us that we’re not worthy of anything. And the way that it is right now, yes, you can come in and fill out a complaint. Well, how wonderful. But I have news for you. When you’re that depressed and you feel that dejected, when you feel that rejected by society, when every day of your life people are telling you that you are worthy of nothing, it is quite difficult to even get out of bed let alone come and fill out a complaint and make sure that it sounds right, and make sure that you’re gonna get people to advocate for you.”

While few in the crowd disputed Burr’s assessment, nobody was pleased with what Burr left unsaid, namely that BOLI is taking a passive role, relying on people to file reports rather than pursuing a more active one that would provide the protections transgender workers need. Alyssa Pagan, who last year moved from Portland but was in town and attended the event, noted, “You cannot expect trans people who are being degraded every day of their lives, who are being forced to live in shame to come to you–to come and get you to advocate for them. I’m sorry, but we are exhausted. The world beats us down every day and tells us that we’re not worthy of anything. And the way that it is right now, yes, you can come in and fill out a complaint. Well, how wonderful. But I have news for you. When you’re that depressed and you feel that dejected, when you feel that rejected by society, when every day of your life people are telling you that you are worthy of nothing, it is quite difficult to even get out of bed let alone come and fill out a complaint and make sure that it sounds right, and make sure that you’re gonna get people to advocate for you.”

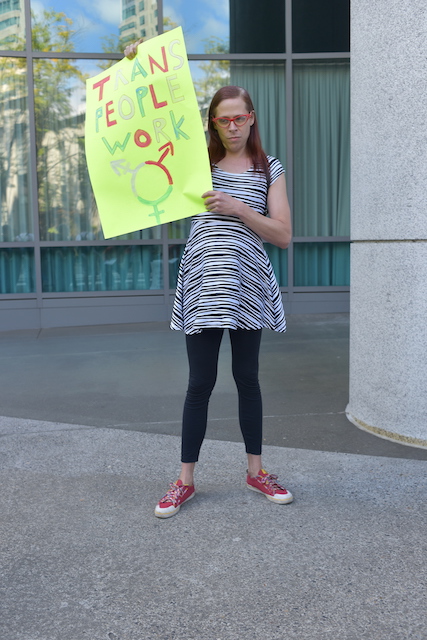

That need for an advocate–not just an organization that will read a filed complaint and perhaps act upon it, but rather one that will actively ensure that workplaces offer non-discriminatory and safe work environments for transgender workers–was expounded upon by numerous people at the rally who had personally experienced or witnessed bigotry against transgender people in the workplace.

“We need to get together and tell BOLI that we want to work,” said rally organizer Brooklynn Clark. We need to tell the State of Oregon that we want to work. We need to tell the employers that we want to work, and let them know what discrimination looks like because I don’t think they really understand like when they say, ‘Why are you going to the bathroom so much?’ ‘Well, I’m on medication that I have to pee off, so I have to use the bathroom a lot.’ So some of these things they might not think are discrimination, but it’s me being a human being, just trying to to live my life. Just trying to be productive and take care of my child and pay my bills. So I really would like to have BOLI as a partner rather than saying that everything’s good and fine and they’re doing everything and ‘trans people: there’s no disparities, there’s no discrimination.’ We know that that’s not true.”

Becky, who described themselves as a non-binary person who passes as cis, said one transgender employee with whom they recently spoke got in trouble “for putting a tagline on their email signature letting people know their pronouns,” while another was recently fired “by managers hostile to her gender presentation.” Still another had her hours cut in half when she “began wearing simple, work appropriate makeup to her job.”

The discrimination Clark and Becky describe does not necessarily find its way to a complaint form, which may lead BOLI to mistakenly believe that conditions are much better than they are. Without an active commitment toward rendering a more just workplace for transgender people–particularly one that reflects the particular needs and desires of transgender people–the success that Burr sees is at best inflated.

If BOLI really wants to know how to slash discrimination against transgender workers and create safer workplaces for them, it would do best to ask them. Otherwise, policy will not be up to the task.

“Unless you bring us into the conversation in a real way,” said Emily, “you can’t do it because you don’t know what you don’t know. You need to hire people–and pay them properly–who have real experience with transgender issues i.e. transgender people. And you need to bring working groups of transgender people to the table where the issues are not only discussed, but where the real decisions are made, where you decide what you’re gonna do and not do. Bring us in and help us have a voice. That’s what we want: a real voice in how we’re treated.”

It would seem there are few better places to begin that conversation than with Clark herself. Clark worked for BOLI for a month but was fired two weeks after declaring she was transitioning from male to female. Clark, who has filed a lawsuit against BOLI for discrimination, said, “The reason that they gave, and what they’re pushing back now, is they’re saying my work quality wasn’t good, but the truth is there were no write-ups, there were no issues. Everything was fine. Everything was good until I told them that I was transitioning. The only thing that I guess I was aware of was when I told them that I work through my mandatory rest breaks. I worked through them. I worked hard. I took my lunch break. And I didn’t take the 15 minute breaks. That’s the only thing they confronted me on and asked me if I would take these breaks, and I told them I would. I’d take the breaks moving forward if they gave me the chance. The next day I was fired, and I sued them.”

Clark stated that she had organized the rally because she knows “there’s more people that maybe don’t have college education that live in Oregon that just simply want to work, that just want to have a job, that want to be productive citizens, that want to contribute, but because we look different, because we sound different, because people are uncomfortable or don’t know a lot about trans people” will not get hired.

Clark stated that she had organized the rally because she knows “there’s more people that maybe don’t have college education that live in Oregon that just simply want to work, that just want to have a job, that want to be productive citizens, that want to contribute, but because we look different, because we sound different, because people are uncomfortable or don’t know a lot about trans people” will not get hired.

Braden presented an even larger picture. Noting that along with Donald Trump–whom she referred to as the “transphobe in chief”–wanting to ban and discharge all transgender personnel from the military, there was the recent Texas “bathroom bill” which, while it did not pass, will surely remain a legislative priority for the state’s bigots, and the failed Republican American Health Care Act which defined being transgender as a preexisting condition. In many ways it seemed the US had “entered an age of legal discrimination” against transgender people. That government discrimination, she said, was “an open invitation for white nationalists and other bigots to attack us as well.”

Rally attendees were also not letting Democrats off the hook. “And if we didn’t learn anything else from this most recent election,” said Be Marston, a shop steward with UNITE/HERE Local 8, “we learned that liberals aren’t always our friends. Sometimes–a lot of times–liberals are the ones that are racist, liberals are the ones being transphobic and homophobic.”

“We can’t rely on the Democrats to save us,” Braden agreed. “Time and time again, they continuously sell us out and side with Trump, our employers, and the healthcare companies who don’t give a rat’s ass whether we live or die.”

Instead, what is needed is real, vibrant democracy and solidarity with other groups fighting for justice. “It’s time to build up mass movements that take up all issues of oppression,” Braden said. “Black Lives Matter broke ground when they took up the issue of trans lives. And our movement can do the same. If we stand with people of color in their fight against police brutality, our movement becomes stronger. If we take up the issues that the immigrant community is facing with their fight against ICE raids and deportations, our movement becomes stronger. If we stand with our Muslim brothers and sisters against the onslaught of Islamophobia, if we take up the issues and struggles of the indigenous people around the world, and if we take issue with how employers treat disabled folk, our movement becomes stronger.”

So up to the tenth floor of the Oregon Building they went, ready to deliver the letter to Avakian. But he was not there. He was, they were told by Deputy Labor Commissioner Christie Hammond, in a meeting. But Hammond said she would gladly deliver the letter to him. Clark demurred, saying she and the rest of the crowd would as soon wait. Hammond’s tone got harder, saying the crowd had to leave because they were cluttering an area of public business, a statement that for many seemed to show the soft bigotry–were they not part of the public?–they experienced every day as transgender people.

Hammond threatened to call security, and indeed she did. There was a standoff, although everyone in the corridor leading to the BOLI office kept to the side, not blocking the elevators and allowing clear and easy access to the office window. Hammond and Burr both kept insisting that Avakian was not and would not be available, but that they would receive the letter for him and review it. The crowd was having none of it.

A few moments later, Pagan turned to Marston and said, “So, when you were talking about liberals and Democrats selling us out, this is an example.”

A few moments later, Pagan turned to Marston and said, “So, when you were talking about liberals and Democrats selling us out, this is an example.”

“Yup,” replied Marston.

“We’re not asking him to sign some legislation.”

“We’re just asking him to accept this letter and think about it, but he can’t give us five minutes of his time.”

“Well, that says everything, doesn’t it?”

“Kinda does.”

Speaking to a KBOO reporter–while glaring daggers at Burr–Pagan noted that Avakian “wants us to believe that he is not some reactionary Republican, and okay, yeah, we believe you, and that means something. But people are really losing faith in people like him who have been touting progressive politics for a long time and running with the Democrat party. And people feel betrayed left and right. And now people are looking at them [the Democrats] with a more critical eye and saying, ‘We’re telling you exactly what it is that we need you to do.’”

About 15 minutes later four police officers emerged. One of them offered to act as an intermediary between the group and Avakian. He was a pleasant sort, although he made clear that if Avakian averred from meeting with the crowd and they then refused to leave, he would have them arrested for second degree criminal trespass. The officer seemed taken aback when Clark stated they did not want a meeting with Avakian, but rather, only wanted to deliver the letter.

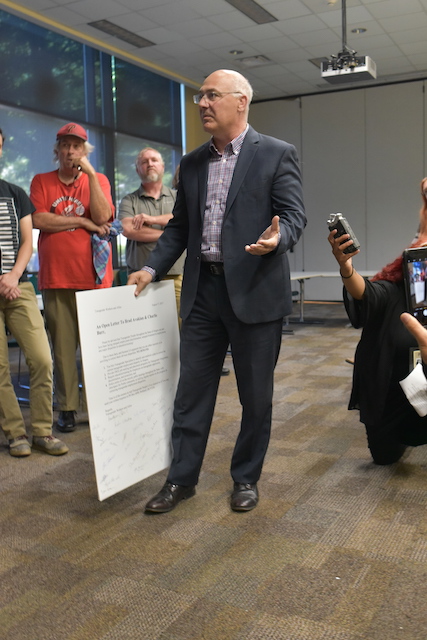

Three minutes later the officer returned and announced that Avakian would receive the letter downstairs in a conference room. The group piled into three elevators, descended to the first floor, and met with the commissioner, presenting him with the letter which was printed on a large placard. Avakian read it. When asked about how he felt about the letter, he gave a predictably tepid response. “I think that you ought to give us a chance to take a look at it and a chance to talk about it. Obviously, everything that you’ve got on here is a core mission of what we do at the bureau which is why I’m always happy to sit down and talk with you about it. So I appreciate the input. I appreciate the passion that you bring to the issue. Give us some time to think about it.”

The actual delivery and response took no more than two minutes.

Avakian’s reply, couched in the safe, non-committal language of a bureaucratic management sort, was in stark contrast to the visceral testimony given during the prior 100 minutes–words that showed the glaring need for BOLI to make a real commitment to protect transgender workers from discrimination.

Their words were hardly safe. As some of Brooklynn Clark’s had shown, there was little safety they could portray in a world where so much security was needed. “We go to the Q Center every Friday and we hear story after story after story after story about homelessness, about sex work, about living in cars, being raped–all kinds of bad things that all we need is just a job like everybody else and then we can have health care. And then we don’t have to commit suicide. So many things if we just have a job. I just want us to work.”

Special thanks to Katy Kates for her help on this article.