Story and photos by Pete Shaw

Story and photos by Pete Shaw

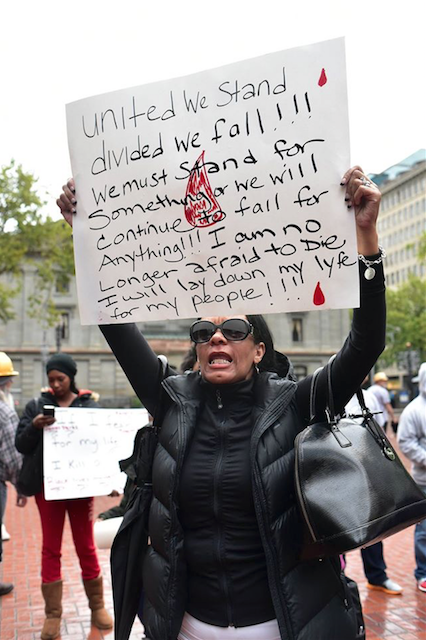

A woman with two children walked down the stairs into Pioneer Square in the early evening of July 7 and began talking about how tired she was. Tired of seeing Black people gunned down by police. Tired of being scared every time her husband, sons, and grandsons walk outside. And most of all, tired that nothing is being done to solve the problem of police murdering Black people with almost total impunity. Her words shattered the somber silence that until that point had only been accompanied by the Friday evening traffic, muted conversation, and the soft impact of a light drizzle falling upon the square’s bricks. She was impassioned, despairing, and resolute.

By the time she finished speaking the crowd that was gathering for a hastily organized rally demanding justice for Black people murdered by police and victimized by police violence had swollen to a few hundred people. A few more people spoke–with the same passion and intensity as her–and then what had become a throng took to the streets.

The direct impetus for the rally and march were the police murders of Alton Sterling, 37, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana on July 5 and Philando Castile, 32, in Falcon Heights, Minnesota on July 6. Both murders were captured on video. Sterling was clearly pinned down when shot twice in the chest, just after a police officer shouted that Sterling had a gun. The gun, in Sterling’s pocket, posed no threat. The police then shot Sterling four more times.

Castile’s death was perhaps even more horrifying. According to Castile’s girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, who along with her daughter was riding with Castile when he was pulled over during a traffic stop, a police officer shot him while Castile was reaching for his license. Reynolds said Castile informed the officer that he had a gun, but was reaching for his wallet when the officer shot Castile in the arm. Reynolds began filming after Castile was shot, and the video showed Castile bleeding out and dying. He was taken to a hospital and soon after arriving was pronounced dead.

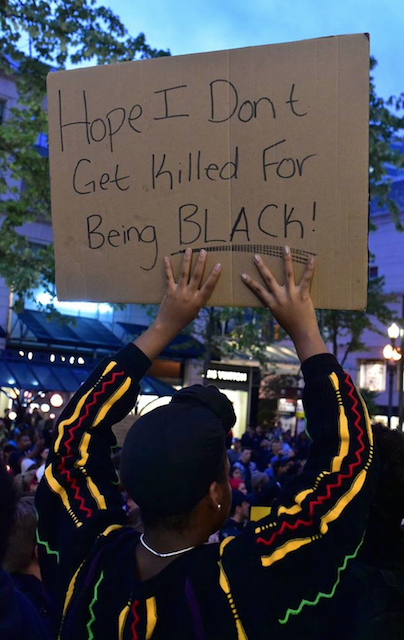

Sterling and Castile’s murders were nothing new. Police, dating back to the slave patrols during the antebellum United States, have long been visiting violence upon Black people and their communities. That violence serves the ruling class, controlling and containing potentially rebellious people whose bodies are largely considered expendable save for the labor they provide. Castile was the 123rd Black person murdered by police this year in a country where police and vigilantes murder one Black person every 28 hours.

Sterling and Castile’s murders were nothing new. Police, dating back to the slave patrols during the antebellum United States, have long been visiting violence upon Black people and their communities. That violence serves the ruling class, controlling and containing potentially rebellious people whose bodies are largely considered expendable save for the labor they provide. Castile was the 123rd Black person murdered by police this year in a country where police and vigilantes murder one Black person every 28 hours.

By comparison to the many Black Lives Matter protests that have taken place over the past couple of years, there was something different about Thursday’s rally. It was suffused with a far greater sense of anger, as if over the past few days some line had been crossed. Of course, that line had been crossed long ago, even before Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and the numerous other Black people murdered by police and vigilante forces, with virtually nobody held accountable for those deaths. Perhaps it took the brutal murders of Sterling and Castile to bring it to the fore. The prevalence of social media, combined with the ease of video recording has brought into living rooms–and palms–the terrorism that has been visited upon Black people by police and other security forces for as long as this country has existed. The intersection of history and the modernity of social media was well summed up in one marcher’s sign that read, “I am a bullet away from becoming the next hashtag.”

The energy pervading the protest found its expression–and perhaps will continue doing so–in solidarity and resolve. After leaving Pioneer Square, the march, which included members of various racial, immigrant, and labor justice groups, wound its way to the Justice Center, a place whose name becomes more farcical with each police murder that goes unpunished. A truck of riot police rode down a nearby street. Many white people in the crowd formed a chain across 3rd Avenue at both Main and Madison Streets, sending a message to police that if they were to bring violence to the gathering, they would first have to inflict it upon them.

Person after person spoke from the steps of the Justice Center about violence they had seen and felt, loved ones they had lost, and the organizing that needed to be done to make change ranging from reforming to abolishing police, as well as the capitalist system that relies on their violence. It was heartbreaking. It was riveting. And it was inspiring.

Ad hoc as it was, the march was messy. It stopped and restarted in spurts. At some points, particularly along major public transit routes, the crowd stopped for a few moments, perhaps readying to sit down in the street, and then moved along again. But that messiness, as Alyssa Pagan later pointed out from the steps of the Apple Store on Southwest Yamhill Street, was what a grassroots democratic movement looked like.

“Because our system that we live under is so severely undemocratic,” said Pagan, “this is what it looks like when you actually try to create a space like this. It looks like chaos. This is beautiful chaos though. The reason that I’m organizing with this group and wanting to keep on having people do mobilizations in the streets is not because I think that is going to be the only thing that saves us, but because I want people to be able to start to see their own power. We talk a lot about it. But this is actually what it’s gonna look like. The reason that it looks so chaotic is because we have no one else, so I’m telling you: this is what hope looks like. And it is going to be messy.”

Quite a few speakers during the event made mention of Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, noting that he was not going to solve the problem of police violence and capitalism. “Don’t tell me about your Bernie Sanders,” said one speaker. “Bernie Sanders is not going to solve the problem.”

Quite a few speakers during the event made mention of Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, noting that he was not going to solve the problem of police violence and capitalism. “Don’t tell me about your Bernie Sanders,” said one speaker. “Bernie Sanders is not going to solve the problem.”

Another speaker echoed and added to that idea, saying, “Bernie Sanders is not going to solve this. We need a revolution from the ground up.” Sanders was mentioned throughout the march, and speakers emphasized the need for change from below because the institutions through which Sanders–or any political party’s candidate–would work, including both the Democratic and Republican parties, are designed to uphold the country’s capitalist norms, which include placing little value on the lives of Black people and other potentially rebellious groups.

“This is a radical movement!” shouted Lamarra Haynes. “And that being said, guess what? The classrooms, the courtrooms–nothing was ever made for Black people. You can’t take back shit that was never yours.”

That point was given great clarity back at the Justice Center when Michael Strickland, a videographer with white nationalist connections who posts heavily edited footage from various social justice movement demonstrations on the internet, began waving a pistol at people who were upset by his presence. Multiple still shots and video show nobody who could be reasonably described as threatening to Strickland’s life, even as he declared otherwise. There was an undercover policeman in the crowd who saw Strickland brandish his weapon. There were riot police in the vicinity. Eventually, after being talked down by some of the rally attendees, Strickland was arrested, handcuffed, and taken to jail, along with, we were told, 5 or 6 magazines of ammunition.

The incident was yet one more stark reminder of the difference the color of a person’s skin makes to their treatment by law enforcement and left witnesses to the Strickland incident to ponder what the outcomes for Sterling and Castile might have been had they too been white.