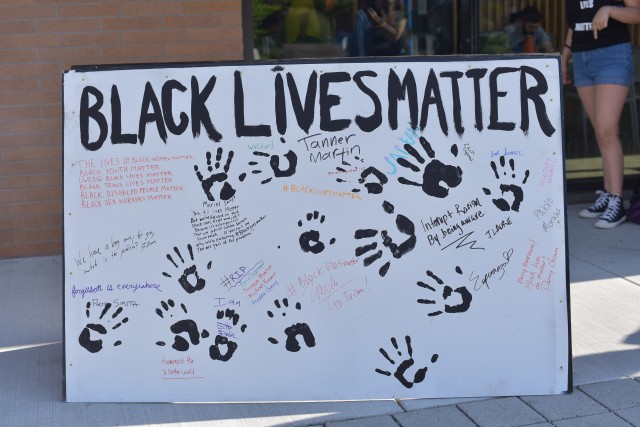

Photo by Lokyee Au

Story by Pete Shaw

The road to obtaining political power is fraught with obstacles, including a variety of institutional forms of racism. As Frederick Douglass once noted, power concedes nothing without a demand. Democracy must be wrested from the powerful through the hard work of those struggling for justice.

As advocates for justice organize communities, they develop goals, strategies, and tactics; eventually they may gain enough leverage that those in power are forced to listen to and act upon their demands. It is a long and tedious process, replete with many setbacks, but it can reap great rewards.

But what do communities do once they achieve some modicum of political influence? Do they keep pushing for more power and more justice, or do they take a more conservative approach, focusing on maintaining what has been gained? As communities push forward, what form will that push take? Can activists achieve more power by doubling efforts within their group? Or do they reach out to forge alliances with other groups?

Many of these issues were addressed in a forum held on Wednesday, June 15. Hosted by the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO) and made possible in part by a grant from Oregon Humanities, Layered History, Linked Liberation: Solidarity and the Role of APIs (Asian-Pacific Islanders) in the Fight for Racial Justice brought together a panel of Chinese American leaders who discussed how they thought the Asian-Pacific Islander community and Asian-Pacific Islander organizations–including APANO–could, according to Lokyee Au, APANO’s Engagement and Development Coordinator, “identify where there are gaps in our work for racial and social justice, and to create more intentional actions to bridge those gaps.”

Au also noted, “APANO has been in coalition with allies and advocated for issues for other communities of color, but we are really intensifying our look at how that solidarity goes deeper, how we call out the wedges that divide our communities.”

The event’s discussion was informed by the recent sentencing of New York City police officer Peter Liang for the murder of Akai Gurley, a 28 year old Black man. Liang, who grew up in New York City’s Chinatown, is the son of Chinese immigrants. On November 20, 2014, while patrolling the New York City Housing Authority’s Louis H. Pink Houses in Brooklyn, Liang fired his gun–it was declared an accidental discharge–and after ricocheting off a wall, the bullet struck Gurley in his chest. On February 10, 2015 Liang was indicted on multiple charges, including manslaughter, of which he was found guilty a year later, along with official misconduct. On April 19 of this year, Liang’s manslaughter conviction was downgraded to criminally negligent homicide. He was sentenced to 5 years of probation and 800 hours of community service.

Liang’s trial raised hackles in both the Black and Chinese American communities. Police killing Black people is clearly nothing new, but indictments, let alone convictions, are rare. A 2014 investigation by the Daily News found that in the prior 15 years no fewer than 179 people were murdered by on-duty New York City police officers (43 more deaths occurred at the hands of off-duty officers). Only three of those deaths resulted in an indictment in state court, with one of those indictments thrown out on technical grounds. Of those 179 documented murders, only once was an officer convicted, but he did not receive time in prison.

It was a complex moment, and this was reflected in the reaction of many people in the Asian American community. Certainly many Asian American people and organizations supported Liang. Given the rarity of indictments, it had to be more than a coincidence that Liang was not only indicted, but convicted and sentenced. For them, Liang was a scapegoat.

Photo by Pete Shaw

However, numerous Asian American organizations–the Asian Pacific Environmental Network of Oakland, Asian Americans United of Philadelphia, the Asian American Resource Workshop of Boston, CAAAV Organizing Asian Communities of New York City, the Chinatown Community for Equitable Development of Los Angeles, and the Chinese Progressive Associations of both Boston and San Francisco–issued a joint statement expressing outrage “that Peter Liang has escaped accountability for killing Akai Gurley.” Describing the downgrading of Liang’s sentence as “an insult to Akai Gurley, his family, and all victims of police violence,” the announcement declares, “we must hold all police officers accountable to continue to fight for violence-free communities and win change in our systems and our institutions.”

The statement continues, “We continue to affirm that if we believe in true racial justice, we cannot excuse an officer for killing an innocent unarmed black man because Peter Liang is Chinese or Asian like us. We know that the strength of our power is fully realized when we stand together with those who also face injustice.” Noting that “other communities of color stood with us against the police killing of Yong Xin Huang in 1995 and other incidents of police brutality and countless critical moments our communities were also hurt,” the signing organizations emphasize, “we have a responsibility to protect our prosperity by protecting ALL families and that means also the family of Akai Gurley who has lost their loved one forever.”

In her introduction to the forum, Kara Carmosino, APANO’s Director of Programs and Strategy, stated that Liang’s trial had “raised tensions around racism, community loyalty, and solidarity” in the Asian American community. Specifically, those tensions were between Asian-Pacific Islanders and communities of color, particularly Black communities.

Scot Nakagawa of ChangeLab moderated the panel. He provided important background for understanding some of the historical relationship between Asian American and Black communities, focusing on the year 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act was signed. That law resulted in the abolition of the earlier quota system based on national origins and created a new immigration policy that while still maintaining per-country limits, focused on reuniting families and attracting skilled labor to the United States.

The legislation, said Nakagawa, was pushed along by the Civil Rights Movement, the Cold War, and the Vietnam War. In particular, the Vietnam War resulted in a shortage of skilled workers in the US such as doctors and engineers, and many Asian immigrants filled those roles. These professionals were, as Nakagawa put it, the cream of the crop. But those professionals helped give rise to the myth of the model minority. Nakagawa noted the irony of this myth being used as an argument against racial justice policies, even as studies show that Asian Americans, despite the promotion of their aggregate economic success, are less likely to receive promotions at work.

The myth is also used against other people of color, particularly Black people. During the Civil Rights Movement, Asian American stereotypes were held up as examples of how minorities should act. According to the myth, Asians were quiet and obedient, while Black people were loud and rebellious. Nakagawa explained that prior to the successes of the Civil Rights Movement, Black people had a lower rate of unemployment than white people. But once they received legal protections, employers began looking for other workers they could exploit, such as many do today with immigrants lacking documentation.

As Black people were pushed out of the labor market and their unemployment rates skyrocketed, President Richard Nixon began getting tough on crime and launched the war on drugs, which was drastically ramped up under Ronald Reagan. As a result, huge numbers of Black people–stereotyped as lazy and prone to crime–were sent to prison (and at extraordinarily higher rates than white people who were committing the same drug crimes). Because of these practices, young Black men became the face of criminality in the US. In contrast, Asian Americans were held up as examples of how minorities should act and what the results could be if people just did what they were told and did not rock the boat.

It was these myths and stereotypes, Nakagawa said, that animated racial tensions that came to the fore during the Liang trial. And it is these myths and stereotypes that stand in the way of greater justice for Asian-Pacific Islander Americans and Black people.

The first question before the panel was what the appropriate roles were for leaders and community institutions in addressing the divide between the Asian American and Black communities. Jennifer Phung, who leads Organizing People/Activating Leaders‘ (OPAL) Youth Environmental Justice Alliance, replied that it was important to “have spaces to talk about the complexities of how we are addressing anti-Black racism in our communities.” Phung noted that when Liang was on trial, much of the Chinese media called for Chinese people to band together and fight for justice, but that she sees this idea of justice as an unhealthy form of nationalism. She explained that organizers ought rather to show how “our struggle connects with other people’s struggles.”

Helen Ying, an expulsion hearings officer for the Parkrose and Reynolds school districts who was a teacher for many years, agreed with Phung, saying organizers need to reach out beyond their communities and seek common ground with other ones. When a rally for Liang was held at Pioneer Square earlier this year, Ying organized a conference call with leaders of Chinese American and Black community groups to foster an understanding of common values. To that end, Teressa Raiford of Don’t Shoot PDX spoke at the rally alongside her Chinese American counterparts in justice.

Photo courtesy of APANO.

Nakagawa then noted the importance of transforming the understanding of solidarity “from ‘me for you’ to ‘we for us.’” To that end, he wondered how the Asian American community could create solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. Kyle Weismann-Yee, who grew up in the Woodlawn neighborhood of Northeast Portland, said that solidarity comes from education. That education must come from leaders, but individuals also have to educate themselves. In particular, he noted the importance of recognizing “Black people’s lived experiences.”

Weismann-Yee said it is important to teach people that it is in their self-interest to forge bonds with others outside their communities, while Phung talked about the importance of recognizing how many of the “rights we benefit from come from prior liberation movements.” Phung also emphasized that people in the Asian American community are also affected by police brutality and police violence, albeit in different ways from the Black community. “Our liberation is connected,” she said. “If the system doesn’t value Black lives, then it doesn’t value us.”

So how can Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders continue building power in solidarity with others? Ying stressed empowering Asian-Pacific Islander students to build relationships with other communities. Phung added that people in Asian communities need to keep building with other leadership groups, that what people are fighting for should lead to “a collective liberation that embodies everyone’s justice.” Weismann-Yee added that it is important to understand where to provide needed support to other communities as well as to “see the shared values that make us complete people.”

One of Aesop’s Fables tells a story of a father with three sons who are heading out into the world. He instructs each of them to gather two sticks. When they return he takes one stick from each of his sons, and he breaks each one individually over his knee. Then he takes the remaining three, but is unsuccessful in his attempt to break them. The message is clear: together, the brothers are stronger.

The solidarity necessary for achieving transformative liberation is significantly more difficult than gathering sticks. But as history has shown many times over, when that solidarity is achieved, the gains are far greater than could ever be accomplished by any group on its own.

Thanks to Lokyee Au for her help in writing this article.

For more information in how you can help build deeper solidarity between communities of color, go to APANO’s website at: http://www.apano.org.