Story and photos by Pete Shaw

Story and photos by Pete Shaw

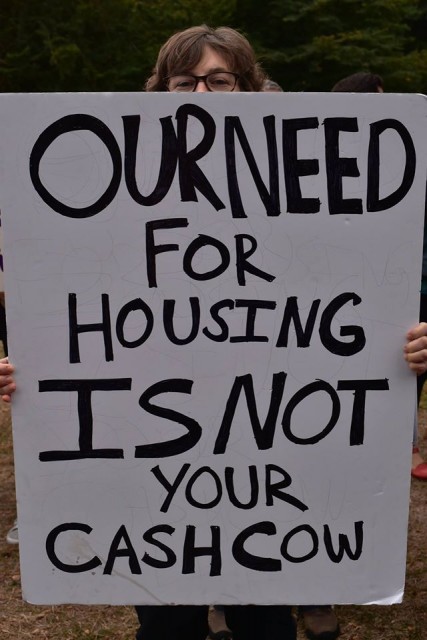

As a debilitating housing crisis continues to plague Portland, those people most affected are organizing against landlords and the laws that work to benefit them at the expense of tenants. On Wednesday December 16, Know Your City (KYC) and Portland Tenants United (PTU) hosted a community dialogue titled “The Rent Crisis: a People’s Perspective.” A panel of five discussed strategies for housing justice in the face of tenant evictions and skyrocketing rents throughout the city.

Back in September, the Community Alliance of Tenants (CAT) declared a renters state of emergency. Soon the City Council followed suit and enacted a series of tepid but important measures that–while not alleviating the crisis–clearly acknowledged the problem and set a path toward a legislative solution. Those measures included requiring landlords to give 90 days notice when raising rent by more than 5% as well as for no-cause evictions.

One of the primary problems facing tenants is that they have almost no legal protection from landlords who want to raise the rent. Portland cannot enact its own rent control measures due to statewide preemption laws, and the two measures mentioned above are already being challenged in court. Opponents of rent control–particularly lobbyists for various landlord trade groups–have argued that the problem is one of supply and demand, and that rent stabilization policies would only create more problems.

On Wednesday December 9, the Oregonian hosted a panel of “concerned citizens and community experts” which included City Commissioner Dan Saltzman and Dike Dame of Williams and Dame development, but did not, according to those who set up the KYC/PTU forum, take into account the needs of renters. Organizers of the KYC/PTU event noted that “while the people on this (the Oregonian’s) panel do make major decisions about housing in our community, this panel clearly fails to reflect the diverse perspectives of working class people who are affected by the housing crisis in Portland.” The KYC/PTU forum was created to give voice to those who were not invited to be on the Oregonian‘s panel.

The night began with the panel being asked why rents were so high. Josh Alpert, Chief of Staff for Mayor Charlie Hales, said Portland was “the victim of our own success.” Citing the “unprecedented level of growth” of people moving here “to live the urban lifestyle,” he noted that for many it was cheaper to live in Portland and commute to work elsewhere, either physically or via telecommunication. This growth, combined with a lack of affordable and family housing, has resulted in a market that has priced people out.

Margot Black of the PTU stated that laying blame at the market’s feet is “the loudest narrative,” but added that people are not making enough money and cannot afford the rent increases that landlords are choosing to make.

Margot Black of the PTU stated that laying blame at the market’s feet is “the loudest narrative,” but added that people are not making enough money and cannot afford the rent increases that landlords are choosing to make.

Katrina Holland, Deputy Director of the CAT, noted that landlords are “just able to raise the rents.” She told the audience that market values are decisions people make, referring to their effect on communities as “economic cleansing.”

Though rent control is subject to preemption under Oregon law, many activists believe it to be a vital tool in protecting tenant rights. Black noted that contrary to the complaints of landlords, rent control does not set unprofitable rents, but rather “does not allow unregulated profit in the same way we don’t allow the water bureau to have unregulated profit.”

While the preemption rule is not set in stone, getting around it would be difficult. Rent control measures must be enacted by the state and are reserved for man-made or natural disasters. In theory, those caveats cast a wide net. Black wondered why “demolitions, evictions, and the lack of demand during the recession” are not considered man-made disasters, asking why these could not be used as grounds for the City to create rent control rules.

Holland and Alpert did not disagree with Black’s assessment, but they also did not think it would pass muster with the state. Holland said the CAT contacted a lawyer about this, and the lawyer was quite sure it was an untenable course. Likewise, Alpert noted that when the City crafted its rules dealing with rent raises and no-cause evictions, its lawyers were very careful to make rules that they felt were defensible.

It seems a difficult tight wire to walk. Clearly there is a problem–the City acknowledged as much in its state of emergency–but solving the problem, at least legislatively, is going to take a series of small steps that eventually lead to larger steps. For example, Holland noted that in the upcoming short legislative session, the CAT would be pushing to abolish no-cause evictions for seniors. Someone in the audience shouted, “Why no-cause evictions for anybody?” Holland responded that the CAT is working on that, but it will require a longer session.

At one point Alpert talked about how when two weeks ago Portland hosted West Coast mayors in a forum dealing with the housing crisis, the Department of Housing and Urban Development expressed interest in attending. During the conference, Alpert said a HUD higher up implied that President Obama might issue an executive order to give cities the tools they need to deal with their housing problems. What that executive order might contain, if promulgated, remains to be seen, but the point was clear that while this is a long process it is a doable one.

The most important aspect of achieving success is nothing new: organize. Vahid Brown, who works with Hazelnut Grove, the community for people without housing near the intersection of North Greeley and Interstate Avenues, noted that the reason why laws and regulations seem to favor landlords and developers is because they are better organized than tenants and people without housing.

Alpert said the state of emergency has given the City time to do its own form of organization. By placing the difficulties faced by people being forced out of their homes out in the open, it helped citizens begin to understand the magnitude of the problem. When the City announced it would use the SFC Jerome F. Sears Army Reserve Center as a temporary shelter, Alpert believed there was less pushback from area residents because of the already declared emergency.

That said, the Sears Building will only be available for six months, at which point, the number of people without housing living on the streets will again rise toward the City-estimated 2,000. It is a temporary solution to a problem that will remain permanent as long as housing is not considered a human right in real, tangible terms.

It’s easy to say housing is a human right, but what does that mean? Chloe Eudaly, who runs the Facebook group That’s a Goddamned Shed and has just started the group Friends of Oregon Renters noted that the Oregonian‘s panelists were asked if housing was a human right, but were pressed little further. “I would like to hear from the panel what housing as a human right means to you because that’s an idea that we’re hearing more and more but is being given very little explanation, and there was so much misinformation spread on that panel last week,” Eudaly said. “If housing is a human right, that means our government and our communities have an obligation to provide it, and we are failing to provide it.”

It’s easy to say housing is a human right, but what does that mean? Chloe Eudaly, who runs the Facebook group That’s a Goddamned Shed and has just started the group Friends of Oregon Renters noted that the Oregonian‘s panelists were asked if housing was a human right, but were pressed little further. “I would like to hear from the panel what housing as a human right means to you because that’s an idea that we’re hearing more and more but is being given very little explanation, and there was so much misinformation spread on that panel last week,” Eudaly said. “If housing is a human right, that means our government and our communities have an obligation to provide it, and we are failing to provide it.”

“Housing is not a commodity,” said Holland. “Housing is not something that should be used for the sole purpose of making money.”

Black added that wealth and investment in housing were ideas that should be looked at in terms of how they impact “the community, not individuals or corporations.”

The City has a few other tools at its disposal. Alpert noted the huge number of “zombie houses”–houses that are empty and not being used, many of which have been foreclosed on by banks–that the City has the power to foreclose on. While the City has not used its power of foreclosure in 40 years, Alpert said it was launching a pilot program of about 20 empty houses which the City would make available to people looking to purchase a home, presumably at prices that would value community over profit.

Alpert said Hales is also changing its policy by which the City conducts sweeps of people without housing. During last week’s torrential rains there were sweeps which Alpert said were not authorized by the mayor. He seemed genuinely shocked that the sweeps happened, saying that the policy should be that during bad weather you “do nothing–leave people alone.” Part of the problem is that there are numerous police forces operating in Portland including the Portland Police Bureau, the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office, the Union-Pacific Railroad police, and the private forces hired by the Portland Business Alliance. Now all sweep requests, regardless of which police force is being called upon to conduct them, must go through the mayor’s office. Alpert said that this did not mean an end to sweeps, but stressed that sweeps should not be used “unless there is an absolute need.”

Brown applauded this policy change, noting that sweeps–or just the threat of them–create great anxiety among people without housing. During sweeps, people lose their possessions, including identifying documents, and find themselves consistently forced to start all over again. In cold weather, sweeps can potentially be deadly, because police confiscate tents and sleeping bags, leaving the houseless to deal with rain, snow and chill with very little protection.

One point touched upon by some panelists was the need to change how people view housing. If, as Holland stated, housing is not a commodity, then what is it? Brown said we needed to start treating housing as a public utility. Black later echoed this comment, and Alpert appeared to nod in approval.

Conspicuously absent was any mention of more militant activity, the work that stresses the system and eventually, to paraphrase Frederick Douglass, makes power concede. A few years ago there was a vibrant housing defense movement in the city that kept people in their homes in defiance of the banks, police, and politicians. It gave some people shelter and breathing room, and more importantly, it organized people and jump started a conversation about housing justice. Some results of that work could be seen at the KYC/PTU forum. If there are to be solutions to this crisis–whether as “simple” as rent control or far more reaching like guaranteeing every person the right to permanent shelter and housing–that militant organizing will need to continue playing an important role.

Near the end of the night, Alpert talked about time he spent following some people without housing around the City to better understand the issues they confront. He said much of their time was spent waiting in lines for showers, doctors or other appointments, and for many other services. For him, it highlighted how inefficient the current system is, and how housing is the basic building block of functional living.

“Without housing,” Alpert said, “human life cannot really happen. When people have housing, that’s when their lives can really start.”