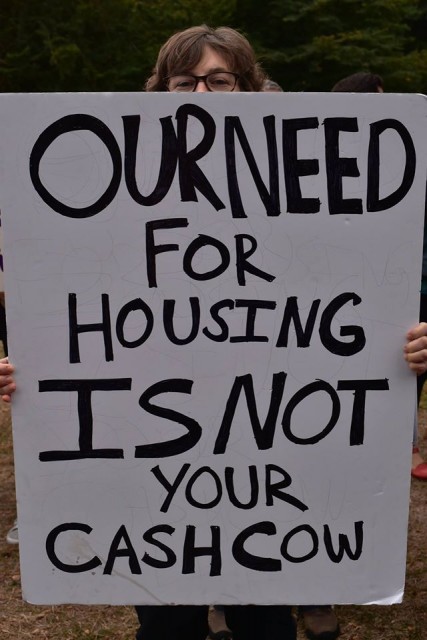

The Community Alliance of Tenants (CAT) declared a renter state of emergency in Portland at a September 15 press conference in Peninsula Park. The CAT–a grassroots, tenant-controlled, tenants rights organization that educates, organizes, and develops the leadership of low-income tenants–called on local officials and landlords to agree to immediate temporary solutions to the housing crisis facing people in Portland who rent their housing.

Solutions proposed by CAT include a moratorium on “no cause” evictions for at least one year and a mandatory notice of at least one year on rent increases over 5 percent. “This summer has seen an unprecedented number of building-wide evictions and rent increases,” said Justin Buri, Executive Director of CAT. “The evictions and rent hikes are forcing responsible and reliable tenants out of their homes.”

Over 200 people attended the press conference. Jeri Jimenez, who, for the past 7 years prior to an August 31 eviction, had called home a unit in the Brentwood-Pinecrest Apartments just across the street from the park, told the crowd, “It’s pretty crazy to know your whole life you’ve worked to make this a better community, and you can be kicked out of your community.”

Jimenez was given a no cause eviction and had to be gone from her home in 60 days. Had she lived there less than a year, her landlord would only have had to give her 30 days notice. After a lengthy and exhausting search that took her as far as Gresham, she found a place in North Portland. However, at over double the $900 per month rent she had been paying, the cost is steep.

As she told the crowd about her struggle, Jimenez mentioned how the media and landlords are playing up the idea of all the “nice new things” that will come with the higher rents, or as she called it, economic redlining. Someone in the audience then shouted, “What good are all these new things if we can’t afford them?”

People who rent housing in Oregon have very few rights, and just as with the fight to raise the minimum wage, Oregon has preemption laws that do not allow local governments to have their own rules surrounding rents. Portland cannot enact its own rent control statutes, and few mechanisms exist to regulate landlords’ increasing rents as they please. Portland also has no rules regarding how much affordable housing apartment developers must set aside when constructing new buildings. With Portland’s population increasing at such a fast rate–according to the US Census Bureau, the population in Portland increased from 2013 to 2014 by 33,500 people, and from 2010 to 2014 over 115,000 people moved to the Portland metropolitan area–the already limited supply of housing has not kept pace with this growth.

People who rent housing in Oregon have very few rights, and just as with the fight to raise the minimum wage, Oregon has preemption laws that do not allow local governments to have their own rules surrounding rents. Portland cannot enact its own rent control statutes, and few mechanisms exist to regulate landlords’ increasing rents as they please. Portland also has no rules regarding how much affordable housing apartment developers must set aside when constructing new buildings. With Portland’s population increasing at such a fast rate–according to the US Census Bureau, the population in Portland increased from 2013 to 2014 by 33,500 people, and from 2010 to 2014 over 115,000 people moved to the Portland metropolitan area–the already limited supply of housing has not kept pace with this growth.

Pastor Mark Knudson of St. Augustana Lutheran Church followed Jimenez saying, “We are in a crisis in this city, and we all know it.” Using the example of an 80 year old woman in the St. Augustana community who was evicted from her home in Lloyd Center and now lives around SE 82nd, Knudson said, “People are coming with money as if this should be determining the neighborhoods in which we live.” In addition to being displaced, Knudson said that woman now spends 95% of her income just to pay her rent.

In an article in the Portland Mercury, reporter Shelby R. King–whose writing on the challenges being faced by Portland’s renters is essential reading–quoted a City Club of Portland report which says that Portland’s fair market rent for a two bedroom apartment is $944, which would require a minimum wage worker to put in 78.5 hours a week just to pay that rent, never mind pay for utilities, food, and other costs of living. And fair market rent is something different from the rent people are asked to pay in reality. According to the website Rent Jungle, the average rent of a two bedroom apartment in May of this year was $1,365. Using the data on Rent Jungle, one finds that from May 2014 to May 2015, the rent of an average one bedroom apartment in Portland increased by about 14% while a two bedroom rental went up 17%

Such points of data were given flesh, bone, and blood when Juan Gonzalez Velaquez addressed the crowd. Velaquez and his family, which now includes his wife and four children, came to Portland 12 years ago. Recently, they were evicted from the same Brentwood-Pinecrest Apartments in which Jimenez lived. “They just took our life away. After that, everything changed.” Velaquez had more to say, but he could not continue, overcome with tears. Diana Pei Wu, Executive Director of Portland Jobs with Justice, then shouted, “Se Puede (We can)!” to which the crowd loudly replied, “Si se puede (Yes we can)!”

A translator continued for Velaquez, reading his story.

Velaquez asked for two more days in his apartment so the family could figure out what to do with their possessions. His request was denied, and Velaquez was told that if he, his wife, and his children were not gone by the proper date, the sheriff would evict them. This resulted in the family having to throw away all their furniture, as well as the children’s toys.

Currently, Velaquez and his family are staying at his sister-in-law’s home. He described his children as being “physically and mentally depressed” and lamented that they were “not able to enjoy summer because day after day we were looking for a place to live.” During that search, Velaquez said he and his family subject to racist language. At the moment, things look bleak for the family, since their only income is from his job waiting tables, and they have no savings.

Currently, Velaquez and his family are staying at his sister-in-law’s home. He described his children as being “physically and mentally depressed” and lamented that they were “not able to enjoy summer because day after day we were looking for a place to live.” During that search, Velaquez said he and his family subject to racist language. At the moment, things look bleak for the family, since their only income is from his job waiting tables, and they have no savings.

CAT’s Deputy Director Katrina Holland then noted that this is a critical moment for Portland’s communities. “We’re losing our lives every day,” she said, and described the effect of the uptick in no-cause evictions and rent costs as an earthquake ripping apart communities. Holland talked about how landlords say they are just charging what the market will bear, but in doing so–as well as rampantly using no-cause evictions–show “no regard” for the lives of tenants.

“The relationship between landlord and tenant should be mutually respectful and beneficial,” Holland said, adding that “tenants’ health” should be considered the same as landlords’ right to make money. She also stated that evicting people “should be much harder and much slower” because it is much harder to find a place than to be evicted.

Holland then rolled out the CAT’s recommended immediate temporary solutions and called on landlords who were not happy seeing communities torn apart to agree to them. “Let’s keep our communities together, stable, and safe. A growing city can exist without displacement.”

But keeping communities together will require the usual ingredients: sustained and effective organization that leaves politicians no choice but to support the rights of tenants–of people and their communities–not to be discarded like so much human refuse. Kaysee Jama, Executive Director of the Center for Intercultural Organizing talked about how for many years now he has been approaching Portland’s leaders about the lack of tenants’ rights that leave renters vulnerable.

“We have broken promises from our elected officials,” he said. “Broken promises each time they say they care.” As an example of that lack of care, Jama asked all the elected officials in the crowd to raise their hands. Despite notice of the press conference being given 6 days earlier, no hands went into the air.

Jama also made a connection between the renter state of emergency and wages. With rents rising as precipitously as they now are, wages must at a minimum keep pace in order for people to be able to afford food and other necessities. This, Jama noted, had less to do with a minimum wage than a living wage. That term living wage gets thrown around often, but in the context of the rally and the stories of people being kicked out of their homes and displaced from their communities, Jama’s words served to remind people that while the push for a $15 an hour minimum wage is necessary, it still is not enough in many places–including most of Portland–to allow people to meet these basic needs, much less live a life with some measure of comfort.

The CAT’s demands appear to be gaining some measure of traction. On Wednesday City Commissioner Dan Saltzman, who oversees the Housing Bureau, issued a press release announcing that he would introduce new tenant protections for Portland renters. Those protections include increasing the notification time that renters have for no cause evictions to 90 days and also increasing the notification time when a landlord raises rents by more than 10 percent in a 12 month period.

Saltzman’s proposal appeared to meet the approval of Mayor Charlie Hales who said, “Dan is right. Protections for renters are entwined in the city’s values of equity and affordability.” Saltzman may be right in spirit, recognizing that more protections for renters are needed, but that 90 days is a long way away from the yearlong moratorium demanded by the CAT. And under Saltzman’s proposal, there is a significant difference from CAT’s insistence that rent raises over 5% have a one year mandatory notice. Saltzman’s press release does not mention how much notice a landlord would need give a tenant when raising the rent over 10%, stating only that “30 days is hardly adequate for renters to budget for the exorbitant rental increases many families are facing.”

Saltzman’s proposal appeared to meet the approval of Mayor Charlie Hales who said, “Dan is right. Protections for renters are entwined in the city’s values of equity and affordability.” Saltzman may be right in spirit, recognizing that more protections for renters are needed, but that 90 days is a long way away from the yearlong moratorium demanded by the CAT. And under Saltzman’s proposal, there is a significant difference from CAT’s insistence that rent raises over 5% have a one year mandatory notice. Saltzman’s press release does not mention how much notice a landlord would need give a tenant when raising the rent over 10%, stating only that “30 days is hardly adequate for renters to budget for the exorbitant rental increases many families are facing.”

During Tuesday’s press conference Holland talked about how disruptive these no cause evictions and exorbitant increases in rent can be. Some of those severances are obvious: paying a higher rent–if you can find a place–moving, uprooting children from their schools and enrolling them in new ones, and leaving behind friends and neighbors. There are also the daily mundanities of comfortable familiarity that must be started anew: Where to get groceries. What parks in which the children can play. A new route to work. All reminders that what was once the norm has now been cast aside.

“This is beyond a crisis,” said Holland. “This is an emergency. Our communities are hemorrhaging, and the bleeding has to stop.”

Want to get involved? Visit the Community Alliance of Tenants’ website at: http://oregoncat.org

5 comments for “Portland Renter State of Emergency Called in Wake of Runaway Real Estate Market”