Story and photos by Pete Shaw

“How on God’s green earth does justice reconcile it?”

Emmett Wheatfall asked that question at least three times while reading his poem at a memorial service marking the five years that have passed since the Portland police executed Keaton Otis at the corner of NE 6th and Halsey. The service was so much more than a memorial for Otis–it was also a remembrance of his father, Fred Bryant, as well as the numerous other people murdered by police. And it served as a five year marker for the living who fight for justice.

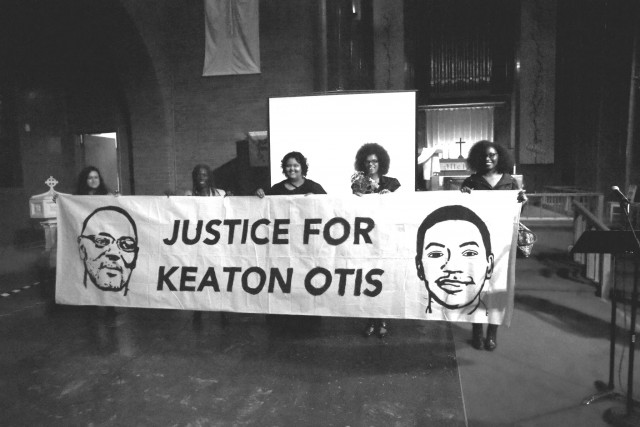

Held at Augustana Lutheran Church, the event was often difficult–overhung with the memory of untimely death. At the same time there was something salubrious about over 200 people gathering not just to recollect in the name of comforting family members and friends who carry on, but also as a recommitment to the struggle for justice. Food was shared and people seemed to leave the sanctuary in a good mood, many smiling.

————

Walidah Imarisha, who along with JoAnn Hardesty has made sure the monthly vigil for Otis has continued since Fred Bryant’s death in October, 2013, hosted the event, noting that it was to honor all people killed by police who have become “holes—missing pieces—in our community.” Imarisha also added that the push for justice for Keaton Otis was part of the larger international Black Lives Matter movement that “we will not forget those who have been taken from us.”

The list of those murdered by police, gone but not forgotten, is long. Some of their memories were brought from the flower gardens, street corner vigils, photos, and other assorted conjures to remind people that no struggle for justice is in vain.

Joe “Bean” Keller, whose son Deontae was gunned down by the Portland police on February 28, 1996, talked about the similarities he saw between Deontae’s death and the police murders of Kendra James and Keaton Otis. In all cases, the corporate media dutifully acted as stenographer for the police, elevating its version of events over that of the victims’ survivors, themselves victims. In Keller’s case, one reporter quoted him as saying his son’s murder was justifiable. He never said that.

The police “justified” Kendra James’ death through the media because they found cocaine in her system when she died, and she had a history of drug problems. However, James was shot and killed when she began driving off in the car that a police officer had pulled over for not obeying a stop sign. She was not driving at the time the police pulled over the car. The cocaine finding was only a retroactive attempt to excuse murder.

Otis was immediately accused of being a gang member. Augustana Lutheran Pastor Mark Knudson stated that when he saw the headline saying Otis was part of a gang—thus justifying his murder—he knew it was false. He knew the pattern. Later, Hardesty would tell the gathered that they “have to stop allowing the media to label our children. We have to question it all because the media does not tell our story.”

Keller has sought justice for Deontae for nearly 20 years, and as he noted, these murders are not isolated events. They send ripples — in some cases, fatal ones. His other son died of lupus not long after Deontae’s death. Keller believes that the lupus became active because of stress due to Deontae’s death. “That one bullet,” he said, “actually killed two people.” He similarly noted that the 23 bullets that killed Keaton Otis, also took Fred Bryant’s life.

Shirley Isadore, the mother of Kendra James, spoke of an encounter Kendra had with the police six months before her death. Not knowing what happened during that event haunts Isadore over 12 years later. After all this time, it seems the one question she really needs answered from the police is, “What did you do to make her so afraid?”

If Dan Handelman of Portland Copwatch could not directly answer Isadore’s question, he provided some insight into why any Black person would fear the Portland police. Despite an Department of Justice finding that acknowledged the poor relationship between the police and communities of color—racial profiling statistics have not changed. “We haven’t seen the change we’re looking for yet,” Handelman said.

He urged people keep fighting, noting that the struggle to hold police accountable is no longer a fringe issue. “We need to take this opportunity to reassert ourselves. Now is the time for us to make the changes we need to see.”

The necessity for those changes were most highlighted by the memory of Keaton Otis’ execution. Otis was shot 23 times by three Portland police officers just moments after three other officers of the same Hot Spot Enforcement Team used Tasers on him. Later, Officer Ryan Foote said he pulled Otis over because “He was wearing a hoodie…He kind of looks like he could be a gangster.”

The police said Otis had fired first–although none of the officers who shot Otis said he had a gun, save for one, who later admitted he did not see a gun. A gun did mysteriously appear on the driver’s seat an hour after Otis had died but it has never been linked to Otis. David Whitfield, who used public records to extensively research Otis’ murder, said, “He never had a gun. He never touched a gun,” and noted how over time the police story “becomes ever more inconsistent.”

So why do the lies persist? “Police and mainstream media,” said Whitfield, “simply don’t want to read the evidence that’s there…We know they are lying because they changed the story.”

None of the seven officers at the site of Otis’s profiling and murder have been held accountable.

In the aftermath of his death, people could be forgiven for thinking that Otis might fade into just another statistic. But Fred Bryant would not let that happen. He began holding a vigil on the 12th of every month at the spot where his son was killed, and he kept fighting until, as Bean said, those bullets killed him too.

The world has become a different place from the one Bryant left. It perhaps started while Fred Bryant was still alive, with the murder of Trayvon Martin, but very clearly the spark to the powder keg came with the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and subsequently, a grand jury not indicting his killer, Officer Darren Wilson. Since then the murders of Eric Garner and Freddie Gray have only put gas on the flames of uprising and rebellion against a police system that brutally oppresses people of color, particularly Black people. Less spectacularly, at least in the corporate media—but as importantly and courageously—Black people are leading movements such as Black Lives Matter and Don’t Shoot PDX, doing the important work so needed to find justice for those who lost their lives and those they have left behind.

The work, understandably, does not always come easy.

———-

Alyssa Bryant talked about how hard it was for her when her brother Otis was murdered. “I didn’t know what I was gonna do,” she said. And then when her father died, she felt destroyed and was ready to give up. But as she noted, Fred Bryant was “a fighter,” and she being her father’s daughter, is a fighter as well. She keeps fighting for justice for her brother and father, and for all victims of police violence.

Fred Bryant made an appearance too. A short clip of him from Jodi Darby, Erin Yanke, and Julie Perini’s film Arresting Power was shown. It featured Bryant remembering how he only found out about his son’s death from the television news, two days after it happened. Talking about the child Keaton Otis left behind, Bryant struggles to say, “What they have left us with is that we have to explain why her dad ain’t here and protect her from the forces that be.”

Wheatfall’s poem, “Keaton Otis: Seven Seconds From Heaven,” created a very unnerving sense of imbalance in its cadences, pacing and dynamics. At one moment Wheatfall was posing uncomfortable questions like “Was Keaton Otis killed for the thrill of it?” and then in the next mimicking the loud, cacophonous, and murderous sounds of tasers and pistols. It was terrifying, beautiful and inspiring. In its densely compacted language, it urged people to keep fighting.

Dr. Pastor Leroy Haynes of the Albina Ministerial Alliance emphasized that this was not a new fight. He would know, having helped organize the Black Panther Party in Texas over 40 years ago, and stalwartly fighting for justice ever since. “If we do our part, if we will not give up,” Haynes said, “we have an opportunity right now to turn this nation and produce a nation that will change police departments across the nation.”

So how on God’s green earth does justice reconcile it? That is a question perhaps best left to the poets and theologians. For everyone else, achieving justice for those who are victims of police violence, the answer is the same old one: keep organizing, and keep fighting.

Or as Hardesty put it, “What you need is the ability to draw a line in the sand and say, in this community we value all life.”

A vigil in memory of Keaton Otis, Fred Bryant, and all victims of police violence takes place on the 12th of every month from 6 PM to 7 PM on the corner of NE 6th and Halsey.

1 comment for “Keaton Otis Memorial Marks Five Years in Ongoing Struggle for Justice, Police Reform”