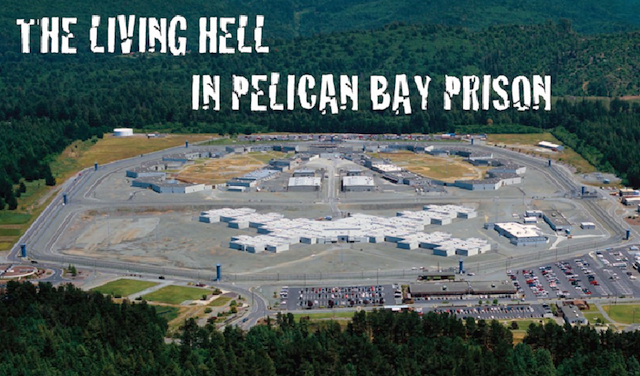

In July, 2011, approximately 1000 of the 1100 prisoners in the Security Housing Unit (SHU) of California’s Pelican Bay State Prison began a hunger strike to protest conditions. The strike lasted three weeks, spreading to another 13 state prisons to include over 6600 inmates.

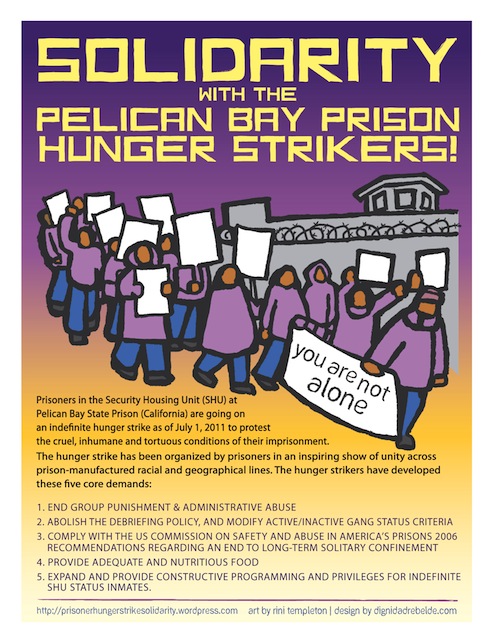

The Pelican Bay prisoners issued five core demands that they required in order to terminate their strike: elimination of group punishments; abolishment of the policy of allowing prisoners to get out of SHU if they provide information on gang activity (gang validation); complying with the US Commission on Safety and Abuse in Prisons’ recommendations on solitary confinement; providing adequate and nutritious food; and expanding and providing constructive programs and privileges for indefinite SHU inmates. Three weeks later, Pelican Bay prisoners called off the strike when the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) said it would make concessions.

In September 2011, after determining that the CDCR had no intention of fulfilling its promise, prisoners across California resumed their hunger strike. Soon, almost 12,000 prisoners had joined. The Pelican Bay prisoners called off the strike on October 13th, when the CDCR announced it would conduct comprehensive reviews of all prisoners whose confinement in SHUs relates to gang validation.

However, once again the CDCR has failed to live up to its word. On July 8th, prisoners in California’s state prisons will again start a hunger strike. At the Red and Black Cafe on June 15th, local activists Walidah Imarisha and Ahjamu Umi led a panel and discussion surrounding prisoner resistance movements and what people can do to support the upcoming hunger strike.

Imarisha talked about the history of prisoner resistance in the US. Like the modern prison system itself, prisoner resistance is largely, although not exclusively, an outcropping of the abolition of slavery. Prior to the Civil War, few Black people were imprisoned because slavery served the same purpose of controlling Black people, families, and communities who might violently rebel against that oppressive institutional structure. But with the Union’s victory, the south’s economy and culture were upended with the formerly enslaved Black people ready to partake in the blessings of liberty.

That, at least, was some of the rhetoric, but as often happens when the lofty poetry of future expectations meets reality, it fell to earth and became harsh prose. The prime example lay in the 13th Amendment to the Constitution which, as the textbooks have it, abolished slavery. Well, most slavery. Here is the actual text of Section 1 of the 13th Amendment: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” That exception in the second clause (“except as punishment”) allowed for the creation of the Black Codes. These laws allowed the white power structure to contain and control the newly freed Black people–a potentially rebellious group. The prison system now served many of the same functions as slavery, providing a captive work force that could be coercively manipulated with the threat of punishment.

Contrary to the saying, history rarely repeats itself, but its currents and eddies seem to swirl back upon themselves, as that which is new bears a striking resemblance to the old, but often with a greater sophistication. The Black Codes are long gone, but they are hardly forgotten. Most recently, for example, they have been replaced by the laws enforced in the War on Drugs. As Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow, has noted, the enemy of the drug war has been racially defined with People of Color making up approximately 80% of those incarcerated for violation of drug laws, despite that fact that white people are more likely to use drugs.

Over 2 million people are now imprisoned in the US, a steep rise from the 300,000 prisoners in the early 1980s, and a number that keeps increasing even as crime rates, including those for violent crime, have remained stagnant or fallen. And while those incarcerated do include white people– particularly poor white people–the number of Black people in jail has soared disproportionately and with no relation to the crime rate. Over 60% of inmates are People of Color, despite the fact that they comprise only about 30% of the US population.

But with oppression comes resistance. Imarisha detailed various prisoner resistance stories, pointing out that the California hunger strikes are part of a continuum of prisoners refusing to submit to inhuman treatment. In 1839, the first women’s prison in the US opened, and very quickly the women inmates rebelled against the horrible conditions. Reflecting the post-Civil War racist underpinnings of the modern prison system, the Black Panther Party called for prison abolition and established a program of prisoner visitation and support. Uprisings at Attica in New York (1971) and Walpole in Massachusetts (1973) showed that, not only were prisoners capable of organizing mass resistance even under the strict rules of prison life, but were also able to create a functioning society that did not require overseers.

More recently, in 2010 prisoners in Georgia used contraband cell phones to organize what to that point was the largest prison strike in US history. Over 10,000 prisoners refused to work until they were guaranteed wages for their labor, a desire no different than many of their ancestors who may have worked on plantations in the ante-bellum years. The prisoners also demanded better educational opportunities, more nutritious food, and greater visitation rights. In short, as with every prior prisoner resistance movement, they wanted to be treated as people, not chattel.

The organizing required to coordinate such actions–even if not using banned items such as cell phones–is intricate and difficult, and does not happen overnight. Imarisha noted a certain irony that the Occupy Movement was blooming during the the second California prisoner hunger strikes in 2011, yet very few connections were made between the two. In Oakland, free people formed support groups, and no doubt played an important role, but the Occupy Movement, which was protesting and seeking alternatives to the unfairness and unbalance of wealth and power in the country and the world was otherwise largely blind to the prisoner’s plight.

Following Imarisha, Umi talked about how free people can support prisoner resistance movements. He first concentrated on what people can do right now to support prisoners, encouraging prison visits and letter writing. Umi also urged people to talk to others about the California hunger strike and break through the often inaccurate media depictions from which many citizens form their core beliefs about incarceration.

Most importantly, Umi told the audience that after July 8 people must continue the organizing that prisoners began. “We’ve really missed the point if we don’t continue their work, Umi said. “You need to organize to make what you want come into existence. We need everybody in a political organization working for justice. If we get enough people doing the same positive thing, we can overcome the system.”

One aphorism often used in praise of the US is that we are a nation of laws, not a nation of men. That is, in theory, the “justice for all” that appears in the Pledge of Allegiance, and it clearly remains unfulfilled. While prisoners are often thought of as the lowest of the low, as a nation of laws, we are still defined by how we treat the least among us. A prison system that has such a racist foundation and is more punitive than restorative, is problematic. Prison reform, more often identified with liberals and Democrats, is not the answer according to Imarisha. She sees little difference between the struggle to rid the country of slavery and the movement to end the modern prison system that was born out of the ashes of slavery. “Liberal ideas of prison reform–that your exploitation and degradation are good for you, are a huge problem,” Imarisha said.

Thanks to Walidah Imarisha for her help on this article.

A rally in support of the Pelican Bay prisoners and their hunger strike will be held on Monday July 8 at 7:30 PM in Chapman Square Park. For more information go to: https://www.facebook.com/events/622999064378532/?fref=ts

For more information on the Pelican Bay Prisoner Hunger Strike, go to: http://prisonerhungerstrikesolidarity.wordpress.com/