Occupy Sandy volunteers feeding FEMA volunteers following Hurricane Sandy

By Nolan MacGregor, Nate Perkins, and Chase Wilson

Last year, Occupy Wall Street emerged from the labyrinth of concrete and steel that is New York City. Three weeks ago, Hurricane Sandy made landfall. In the wake of the storm which left millions without power, thousands without shelter, and more than a hundred dead, Occupy has found a new arena for struggle and a resurgence of public participation.

While President Obama was initially applauded for his handling of Hurricane Sandy, in the week following the storm it became clear that the most that could be said about the president was that he responded to disaster with more charisma and political sensitivity than his predecessor did after Hurricane Katrina. As for providing materiel relief to those affected, neither federal agencies nor mainstream charity organizations have been successful on nearly the same scale as communities working through social media and horizontal networks of mutual aid.

This system of mutual aid has a name: Occupy Sandy.

In response to the devastation in New York, Occupy Wall Street organizers expanded the focus of activist networks formed throughout the past year to the task of providing material relief that corresponds directly to the needs of communities affected by the hurricane.

We Got This (Occupy Sandy) from Alex Mallis on Vimeo.

Learn more about Occupy Sandy and how to contribute here.

Praise for these efforts is not limited to the backwaters of alternative journalism. Numerous mainstream publications, from the New Yorker to the New York Times, have highlighted the effectiveness of Occupy Sandy in contrast with the failures of established disaster relief organizations.

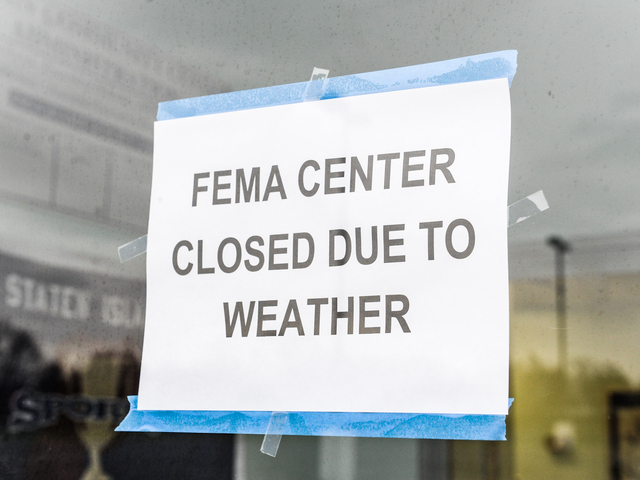

Sign on the office of the Tottenville FEMA center in Staten Island. Photo by Stephanie Keith/DNAinfo

Occupy Sandy volunteer Sofía Gallisá Muriente recently spoke to The Nation about an interaction she had with the National Guard. “Two nights ago, they pulled over and gave us a truck full of water and meals, which really startled all of us because it means they recognize we have things under control in a more efficient way than they do.”

The NYPD, FEMA, and the National Guard have recognized that community power can succeed where vertical associations fail. Though at first the recognition was isolated to individuals, the state has been pushed to officially recognize Occupy Sandy efforts as legitimate. At the beginning of November, FEMA and NYPD officers joined community members and activists in chanting “We are unstoppable, another world is possible.” Then, on November 10, Occupy Sandy hosted a meeting attended by community leaders, a representative of Mayor Bloomberg, and members of the NYPD.

Where FEMA workers and the crimson hoods of the Red Cross are nowhere to be found, thousands of people, many of whom had no prior interaction with Occupy groups, have provided or been provided with food, clothing, water, emergency shelter, and power for phones to contact loved ones. This is not a case of charity. The Occupy Sandy effort is a clear example of communities collectively addressing their own needs, and becoming stronger in the process.

These connections must not be the side effect of a transitory, temporary effort to return to normalcy. To be clear, normalcy under late capitalism means a constant state of low-intensity crisis, a slow-moving storm that sweeps people from their homes and deprives them of their livelihoods in a way too subtle and institutionalized to capture media attention. Occupy Sandy is a continuation of efforts to build lasting structures of popular, horizontal power. It picks up where established institutions, either by accident or design, have failed and will continue to fail to address the needs of the people.

Thankfully, it seems that the implications of Occupy Sandy will go far beyond the relief effort. In Red Hook, a Brooklyn neighborhood hit extremely hard by the hurricane and still without power, a mesh net that was set up in 2011 has allowed residents to seek help over social media and communicate with the outside world. Occupy Sandy organizer Shawn Carrié tweeted the following sentiments on November 12. “I think other people can also feel this, that in #RedHook we’re working with something bigger than @OccupySandy, it just doesn’t have a name”.

The trend toward the development of parallel institutions of political and social empowerment is not limited to New York, nor to the narrow context of disaster relief. Since the very first days of the Occupy Movement, utilizing models of horizontal social organization has been a primary focus. The decision-making model of the General Assembly employed in Zuccotti Park (NYC), Main St. (Portland, OR), and thousands of cities around the world stands in stark contrast not only to the hierarchical methods of social control employed by the State, but also to the operation of many activist organizations and unions, in which a few people make decisions and put them into action on behalf of the rank and file. Creating participatory institutions is essential not only for timely and appropriate relief in the wake of cataclysmic events, but also to build powerful alternatives to the exploitation that is neoliberal capitalism.

It must be explicitly recognized that when people organize to ensure that their needs and the needs of those around them are met, they are not just improving their immediate environment. In bolstering the political legitimacy of their respective communities, they consequently delegitimize institutions that perpetuate existing power structures. The growth of a revolutionary movement requires the cultivation of a widespread awareness that to empower communities is to seize power from the State, that such a process is conducive to the betterment of all life, and should be pursued with the goal of overtaking the State (in terms of political legitimacy) and the financial sector (in terms of economic control).

The concept of creating parallel institutions that operate through participatory decision-making and mutual aid is applicable to the movement in its present forms and provides an answer to questions of what the movement wants and how it plans to move forward.

The proliferation of models for localized, participatory decision-making and community empowerment is already wide. The efforts that constitute Occupy Sandy are only the latest and most prominent examples of how this movement has become more than a collection of issue-based agitators or a series of protests. Further, global efforts to liberate living space, achieve food sovereignty, defend against police terrorism, and support workers’ struggles were underway long before the Occupy Movement.

A prerequisite to social revolution is a situation of dual power. The American Revolution of 1776 had its Continental Congress. Elected members of the Irish revolutionary party Sinn Féin had their First Dáil. Venezuelans have their communal councils. We have our Assemblies. Ours must be forums not only for coordinating demonstrations, but for organizing the primary aspects of social life.

Will we recognize and accelerate our steady advance toward situations in which our institutions—the Neighborhood/General Assemblies, Spokes Councils, and other horizontal models—directly confront the decaying and increasingly destructive institutions of neoliberal capitalism?

In order to move forward, both organizers and the broader public must internalize that we are not simply protesting corporate greed, but creating new ways of life: methodically, intentionally, and with a coherent vision. We work for a world of self-determined communities that control their means of production, a world where individuals have agency over their lives, and where the cumulative result of millennia of human development is used for the benefit of all life.

2 comments for “#OccupySandy: Disaster Relief and Dual Power”