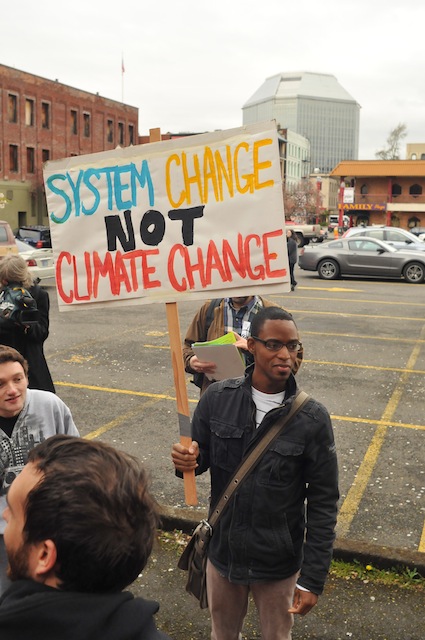

Story and photos by Pete Shaw

If you’ve got the green, being green seems to be all the rage these days. You can hop in your Prius with some canvas shopping bags, head to the rainwater recycling, solar-powered supermarket, buy some Coca-Cola in a reduced plastic bottle and, while enjoying your caffeine high, feel good about not contributing to the greenhouse effect and its resultant climate change. It’s reasonable enough, but in the end, if it is an end, does it do much good beyond making your personal space a little more livable?

Your Prius is composed of raw materials – many of which are toxic – that were harvested under conditions approaching slave labor. That supermarket still sells a lot of plastic, and regardless of whether or not that Coca-Cola bottle contains less, it’s still a petroleum-powered vessel that will neither decompose nor get far beyond a recycling center dumpster. So oil, a substance whose existence has often proved a curse to those who live on top of it – ask someone from Iraq – is involved in the manufacture and deployment of both the Prius and the Coke.

The Green Economy was certainly born out of necessity. Climate change is a reality, and many financially well heeled latecomers to this reality appear willing to consume in a manner that will mitigate global warming.

According to Kari Koch, who recently attended the People’s Summit held in coordination with the United Nation’s Rio + 20 conference in Rio, Brazil, the Green Economy is also a sham. At a presentation at Portland Community College on July 17, Koch talked about getting together with a group of people – the rabble barred at the threshold of climate conferences – who are working to create alternatives to the Green Economy – alternatives that will offer real solutions to climate change; reflect a respect for local populations; and give justice to those whose resources, livelihoods, and health are meaningful to the European and U.S. version of the global economy in direct proportion to their ability to help prop up our standard of living and global hegemony.

But what are the odds of success? Sometimes it seems damn impossible to believe that the human species will be extant 200 years from now, what with all the climate models predicting weather likely to make the hurricanes, tornadoes, storms, heat waves, floods, and droughts of recent years seem like a walk in the park. These weather events are disastrous enough for us, but much more catastrophic for nations lacking our infrastructure, in many instances, because we have subverted its development in order to advance our own grasping industrialization.

Touted as a panacea to climate change, the Green Economy actually is old wine in a new bottle. Koch noted that, as a capitalist solution, the first purpose of this Green Economy is to generate profit, rather than solve the problem of climate change. It is, in fact, a Greed Economy, and thus not surprising that some of the proposed “solutions” instead create further problems.

For instance, there is no such thing as clean coal, and natural gas is just another term for fracking – which uses large amounts of water, such that it might leave some farmers scratching their heads in this summer of drought. Oh, and ask the folks in Fukushima, Japan, how they feel about nuclear power.

Koch tied together the connection between the Greed Economy and the various aspects of imperialism that have always accompanied capitalism and related greed-based economic systems. In Colombia, for example, water is quickly becoming a profitable commodity and the Colombian military is used to protect its extraction and repress protest, often from posts along waterways.

The homogeneity that has become a defining characteristic of U.S. capitalism – think McDonald’s, which makes Big Macs tasting the same everywhere – is being imposed upon people in other countries. Land that could be used for a vibrant agriculture, one that includes many animals and crops whose various biological interactions produce food to sustain body and mind, is often used for growing monocultures such as palm oil, coffee, or cacao that provide nearly zero nutritional value, in addition to the fact that they are mostly being shipped to U.S. and Europe.

And the problem with so-called green employment, said Koch, is that it ends up being a Band-Aid approach to the problem, because consequences are of little concern save for how they impact profit.

So what was Kari Koch doing in Rio? Not attending, for one, the United Nations affair. Time and again, starting with 1992’s United Nations Summit on Sustainable Development, Koch said she has noticed these conferences deliver the same outcome: lots of nice, powerful language, but no results. Very strong principles came out of the 1992 conference, supporting the idea of differentiated but common responsibility (that is, we are all responsible for combating climate change, but those nations that consume more contributing resources bear greater responsibility), as well as stating that people living under colonialism should have their resources protected.

But from that point, Koch noted, reality moved forward from a corporate, nation state perspective, which views that resources as a commodity to be exploited for profit. Further conferences, beyond the nice words for public consumption, featured “unelected and unaccountable people negotiating non-binding treaties in bad faith,” often centered around finding ways of forcing other countries to take responsibility for corporate greed. Thus Koch came to believe the real purpose of these conferences was for corporate shills to entice the governments of resource-rich nations to act as a buffer between corporations and the peoples’ movements opposed to the theft of those resources.

For years, protesters have attended these UN summits in an effort to shut them down or play an inside-outside game with young people inside speaking of their diminished future (some words of which would hopefully shame some of the delegates and get them some corporate media attention, while outside people would protest. Twenty years on from the 1992 conference, the effect of this strategy has been indiscernible at best.

So Koch joined the People’s Summit this time, a mass of people and organizations “uniting against the commodification of life and in defense of the commons” with a goal of exposing, promoting, and making visible the invisible people affected by climate change and promoting alternatives to the Greed Economy. Coming from the perspective that there is no one correct answer, Koch said one of the overarching goals of the People’s Summit was to build connections and relationships towards an international collaboration that would result in alternatives to capitalist solutions.

Emphasizing the People’s Summit call for solutions that respected the rights, needs, and dreams of all people, and recognizing that those will be different from people to people and place to place, Koch said, “We need to figure out what this new world looks like. It’s not the homogenous world capitalism promotes.”

Koch said there were over 800 workshops at the People’s Summit, as well as a slew of marches and rallies. One march, Koch said, visited a flovella (the Brazilian term for a shanty town) that was being cleared for “development.” Brazil will host the Olympics in 2016, and already flovellas are being razed. leaving the people – or ‘dirty elements’ as they are called – to fend for themselves. The Olympics are an extreme example since they are held every four years and not often in the same country, but these violent removals also take place for more general development such as building a steel mill.

Koch also encountered many people who were excited about the Occupy Movement, many of whom had also criticisms about it. But they were taken aback, when Koch observed that many of her fellow U.S. Occupiers saw the movement as racist. While this has been sometimes true, the U.S. is a white-faced country and to people outside, the fact of a white-faced movement “rising up and tackling industries hurting the world” was a “breakthrough moment.” That moment, Koch said, needed to become a real movement that modeled and interconnected with local struggles throughout the world – one that accepted responsibility for challenging power structures within the U.S., eventually taking them over and making them work for justice, not corporate profit.

Like all fights against the entrenched power elite, solidarity is key. Never an easy feat for something as relatively small as Portland’s Occupy Movement, the task seems all the more daunting when talking about international unity. Part of the solution, Koch noted, is making a mental shift away from capitalist and imperialist propaganda. For example, the People’s Summit emphasized that there is no one right answer, but for each of the many right answers there must be respect for those formulating them, and the developed world must take responsibility not only for respecting those rights, but also for mitigating the damage our resource appetite has cost.

Koch also emphasized the need for long term thinking, asking, “How can we all work together? Where are we going? How do we connect struggles into a long term movement instead of a short term march?”

Part of the solution will include getting grassroots movements on the same page for the long haul – think in the magnitude of a 50-year movement. Working collaboratively is essential, as is going outside comfort zones to build alliances. Ultimately, a 50-year movement requires commitment to a long term process, through both good and bad. But if groups can reach out and work together, the goals laid down at the People’s Summit – an end to the use of fossil fuels, a just transition to local economies, and a taking of power instead of just protesting it – are attainable. As the saying goes, they have the guns, but we have each other.

In summing up, Koch expressed what lies ahead. “We need to build our struggles and capacity,” said Koch. “We need to be ready for what comes after power falls. We need to drop everything and collaboratively figure out how to solve problems.”

1 comment for “The People Cook Up New Approaches to Global Warming”