This article was original published on The State.

by Adam Rothstein

Before I even finish writing the phrase, “zombie apocalypse”, there is a good chance you’re horrified—by culturally over-determined boredom, rather than by monsters. The fantasy of the zombie outbreak is becoming ploddingly dull, fired into our crowded consciousness again and again, like rounds from a semi-automatic shotgun. But the zombie monster is not the apocalypse. An apocalypse is literally a revelation, not the end of the world itself. In human literature what is revealed is most often of the future, the ultimate climax of which is the end of recorded history. There is no temporal narrative without a close to that narrative, and as we study this dark paradox, we watch for that end.Since shambling onto the screen, the zombie has resonated. There is something catching in the idea of a nemesis that is multiplicitious: easy to kill in the singular, but unstoppable in the plural. The zombie is a monster of our own production. Unlike mythical beasts risen from the earth, or alien antagonists visiting from afar, the zombie is an epidemic spreading amongst us, caused by pollution, conspiracy, industrial accident, or contagion. We once feared miasma, or bad air as the cause of our collective societal sickness. While we’ve discovered the germs responsible for cholera and malaria, death by undifferentiated plurality is a less understood malaise threatening our history.

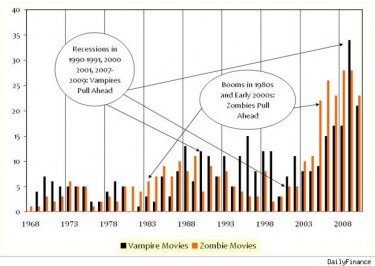

Perhaps it is no surprise that the link between economics and zombie films is fertile ground. Economics continues to be a poorly understood pollution we inflict upon our societies. Corporations, secretive nation states, and otherwise ethically derelict societies are often the cause of zombie-outbreak in fictional stories. There is an uncanny echo to the unstoppable, plodding undeadedness of capitalism’s animate corpses: real estate short sales, the outbreak of high-frequency algorithmic trading, and National Banks with little ability to control interest rates or inflation.But it is not with the fictional monsters’ gruesome violence that we are obsessed. It is worth noting that the recent episodes reported as potential “signs of a zombie apocalypse” are primarily instances of cannibalism, not zombification. Cannibalism has a long recorded history both within our species and outside of it. In all recorded instances of human cannibalism, it is always either in-group or out-group members of the cultural entity which are eaten, but never both. This sort of violence might be horrible, but it is coded with identification. Similarly, bloody violence is often the central content of our historical textbooks, not the sign of its dissolution. War, not peace, determines nation states. And similarly, an in-group is using cannibalism to mark the fantasy of zombie apocalypse with meaning.

What we talk about as zombie apocalypse is not violence, but the fear of joining that overwhelming mass that stands against social codes of identification. We cower in the face of the chaotic horde of undifferentiated particles, not held in place by culture or history, let loose and run rampant in the streets. The oozing pus and sucking wounds are only the icon, the marking by our culture of what it would like us to find truly horrifying: vast numbers of people without names, jobs, or other cultural ranking, walking in the streets without regard to traffic, plunging through architecture without notice of its design, smashing televisions to the ground without responding to advertising, as faceless as if masked, as nihilistic as if smashing shop windows for pleasure. There is nothing so monstrous to culture’s value system as the zombie bloc.Slavoj Žižek has famously quipped that we can more easily imagine the end of the world than small changes to the economic system. In the instance of the zombie apocalypse, what is metaphorically revealed is that a change to the cultural inscription process of the economic system would in fact be the end of the world. How does one keep a zombie beholden to its credit score, or its student loan debt? How can one satisfy a zombie with minimum wage, party politics, and populist sporting events? If all at once our cannibalism reversed, targeted the standard in-group as the out-group, the warm body known as “the working class” would tear off its own hardworking arms in furious stupor. Refusing to work, and yet still walking—undeadedness is a permanent general strike.

Our endless repetition of the zombie apocalypse is our own revelation. We would sooner saw off our own leg than join the undifferentiated lumpen-proletariat as it roams through the streets. In every zombie apocalypse survival guide, in every first-person shooter video game, and in every blood-splattered late-night horror film, the cultural message is clear. “Human beings! Gun down your friends and neighbors, before abandoning your auto loans!”And perhaps such a Marxist narrative is a bit over-determined as well. We hardly require zombie films to engage in a counter-revolutionary impulse. And yet, the zombie apocalypse is purely fantasy. There are no zombies. Our continued cultural self-cannibalism, on the other hand, is history.