By Pete Shaw

Immigrant deportation not only tears families and communities apart, it’s one of the most divisive political issues in the U.S. today. Those expecting the Obama presidency to result in fewer immigrant deportations have been bitterly disappointed. Recently, that figure passed the million mark, a number that exceeds the deportation statistics in both G. W. Bush terms combined.

“When Barack Obama became president, many of us expected a kinder, gentler immigration policy,” said Elliot Young, director of Latin American Studies at Lewis and Clark, and one of three featured speakers at an Insecure Communities forum. The April 13 event, held at the Unitarian Church, provided an opportunity for the 120 people present to connect with organizations seeking an end to deportations by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agencies (ICE). The panel also covered immigration history, enforcement, and anti-immigrant backlash, as well as the moral and ethical components of detentions, and how communities can resist ICE and create secure communities through education and action.

Immigration has a long and complex history in the U.S. Immigrants founded and wrote the rules for the country and took most of the land, a process of exploitation that continues today. Young emphasized that despite today’s anti-immigrant hysteria, the percentage of immigrants composing the population of the U.S. is not unprecedented. Between 1860 and 1920, the percentage ranged between ten and fifteen percent, peaking between 1900 and 1920. Today’s foreign born population makes up twelve percent of the total, and only a third of those people are without documentation.

Young emphasized the forces driving immigrants to the U.S., particularly the historical and causal links between U.S. wealth and the relative poverty of Central and South American countries. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), for example, allowed U.S. farmers to dump their corn on the Mexican market–corn that sold for less than the corn produced by Mexican farmers. As a result, many farmers left their land, but Mexican cities offered few jobs, forcing them to the U.S. to earn money to support their families back home. Immigration was a rational economic decision.

Rene Sanchez, visiting professor of theology at the University of Portland, spoke about growing up as the son of migrant workers as well as his experiences as a farm worker. Emphasizing the importance of using our power and privilege to tell the stories of immigrants, particularly those in poverty, Sanchez urged the audience to “disrupt, remember, and resurrect,” three steps he believes will lead to a more just society.

Of the poverty he has experienced and witnessed, Sanchez noted, “Poverty is grinding. It’s a terrible experience. It’s brutally dehumanizing.” Sanchez came to the realization that, in seeing this poverty, its effects, and its connection to a hierarchy that funneled wealth and power upward–while denying the humanity and dignity of those who received almost none of the benefits–he was witnessing sin.

Sanchez, referencing the idea that Jesus taught love of neighbor, said the first step towards justice is recognizing disruption. “We’re all connected to immigrants. We have to accept that the wealth of the United States has come with profound disruption to our neighbors.”

Recognition of disruption is then followed by remembrance. Sanchez reminded the audience how, after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, it was popular among the political elite to blame some nebulous “they” who “hated us for our freedom” for national insecurity. This “they” very quickly became all whose religion was Islam, or, sometimes, merely those who fit the corporate media stereotype of those whose religion was Islam. “Maybe ‘they’ hate us because we don’t remember them,” contended Sanchez. “We don’t tell their stories.” Illustrating this, Sanchez observed how September 11 in the U.S. is almost exclusively equated with September 11, 2001. Yet in Chile, the day is remembered for the U.S. backed and engineered coup that overthrew Salvador Allende’s democratically elected government in 1973 and brought to power a brutal government that terrorized the Chilean people for many years. The Chilean story–as well as the similar stories of people in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and numerous other nations whose lives were disrupted by U.S. foreign policy–is remembered well by its victims, but remains on the margins of U.S. history, a place where many have benefited from the disruption.

Finally, there is resurrection–achieving a deeper spiritual reality, as Sanchez put it. Resurrection requires knowing your neighbors’ struggles and trials and recognizing your relationship to them. Those of relative power and privilege must become voices of resurrection, because those voices can be heard and are “an opportunity for America to learn how to love and love well” and achieve a more just world.

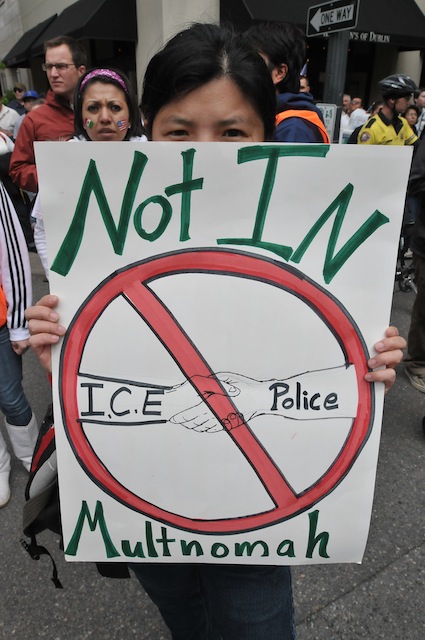

The final speaker was Shizuko Hashimoto of ACT for Justice and Dignity, a legal assistant at the Immigrant Law Group, and one of the initial organizers of the Safe Communities Project Coalition, formed in 2009 to monitor and advocate against unnecessary collaboration between police and ICE in Oregon. Hashimoto emphasized that the cooperation between police and ICE is not ahistorical–that we once had slave patrols which functioned to intimidate a group of people and co-opt their labor.

When Arizona’s State Bill 1090 was being written, Hashimoto said immigrant rights activists in Arizona warned groups elsewhere that it was just the beginning. Since then, numerous other states have passed their own anti-immigrant legislation, some more draconian than the Arizona version.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the detention center. As stories of ICE raids, and the devastating results of deportations that separated families became known, the corporate media turned sympathetic. As a result, said Hashimoto, “people started asking what deportations do to communities. ICE backed off, finding out that ‘people are not as racist,’ as they thought.”

In response, ICE sought to change the narrative by focusing on immigrants as drug dealers and violent criminals and generalizing this to the whole immigrant population. By 2006, because of racist legislation, such as Wisconsin representative James Sensenbrenner’s Border Protection, Anti-terrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005, “immigrant” had become synonymous with people from Central and South America. ICE successfully rebranded immigration as a security issue, criminalizing an entire group of people.

Statistics show that roughly half of the people deported during Obama’s tenure have been brought into ICE’s jurisdiction for infractions as minor as speeding tickets or no violation at all. Over the past three years, less than 20% of those identified as undocumented were arrested for felonies. The remainder–most of them deported–were arrested for misdemeanors.

“Whether we like it or not, people of color are being criminalized, and stereotypes are being reinforced,” said Hashimoto, noting how many corporations such as Wells Fargo Bank, Corrections Corporation of America, and Geo Group are making profits by denying people their freedom. “Some of the biggest atrocities in history have started with dehumanizing. If this keeps going the way it’s going, where does it go next?”

Aeryca Steinbauer, an organizer with CAUSA, explained some of the harmful results. “Fearing interactions that could lead to time in the immigrant detention system and possible deportation, even when the person may be documented, people do not call emergency services when they need help, something that makes us all less safe. And when a family member is deported, that disrupts the whole family and is traumatic for all involved. The left-behind spouse now has to struggle with single parenting, and children are left wondering what happened to their mom and/or dad.”

Movements have arisen nationally, organizing communities to fight the collaboration between police and ICE. Hashimoto noted that in communities that partner in the Secure Communities Program (the partnership between police and ICE), police and ICE claim they are just sharing data when “in reality it leads to racial profiling.” When an ICE hold is placed on a person, police can pick her up, take her to a detention center, like the one in Tacoma, WA, and keep her in custody for up to 48 hours. This leaves two avenues for action: “Either we convince ICE not to hold her, or we convince local police not to honor the hold.”

Immigrant rights groups have had some local success. In March, emphasizing the costs of using local funds to enforce federal immigration laws, activist organizations pushed the Multnomah County Board of Commissioners into passing a resolution calling for an end to ICE’s unjust local deportations. Steinbauer praised the commission, while also acknowledging the long road ahead.

“They took a great first step in March by passing a resolution expressing their deep concern about deportations and the separation of families, as well as the damaging effect this has on trust between immigrant communities and local law enforcement,” Steinbauer said. “There’s a lot more work to be done, though, and we are continuing that process by meeting with local elected leaders. The overall solution, of course, is just immigration reform that provides a path to citizenship for people, to bring them out of the shadows. In the absence of that reform we are exploring other solutions, such as a resolution adopted in Santa Clara County, CA, which stated that they would not honor ICE detainer requests except under certain conditions.”

Hashimoto observed how this criminalization and otherization of immigrants–their dehumanization–goes largely unquestioned and depends upon individuals choosing to be judgmental, rather than thoughtful and empathetic.

“They’ve convinced people that a bunch of people are criminals,” Hashimoto said. “They are not criminals. They are mothers and fathers. We need to educate, educate, educate. Talk about loving the other. Live it. Mean it. ”

More information on the Safe Communities Project Coalition is available from CAUSA, from ACT for Justice and Dignity, and from VOZ.